Philanthropist Sally Morrison on her life’s missions

You’ve gotta give it to lifelong philanthropist Sally Morrison – she’s one very special woman.

You’ve gotta give it to lifelong philanthropist Sally Morrison – she’s one very special woman.

WORDS MONIQUE BALVERT- O’CONNOR PHOTOS JAHL MARSHALL

It’s been 18 years since you first wrote about me,” says Sally Morrison. “Frog Cottage,” she prompts, and I’m transported back to the character green- and-white home she owned on Tauranga’s Devonport Road.

Actually, there have been several stories over the years highlighting her gardening prowess, beautifully bedecked homes and more. I may be slightly vague on the details, but I forgive myself, and for a good reason that has nothing to do with the passing of time. Quite simply, such memories are superseded by my recall of Sally’s philanthropy. What I remember with great clarity is Sally’s volunteer work at a Vietnamese leper colony.

We settle down to chat in Sally’s Mt Maunganui apartment, where she tells me that the leper colony chapter of her life started back in the 1990s. A fellow Tauranga Sunrise Rotary Club founding member spoke to her about his auntie, a Catholic nun, and her work in Vietnam. Sister Sheila O’Toole went to Saigon during the Vietnam War, was held hostage in a prisoner-of-war camp, and was one of the last people to depart from the US embassy in 1975. She returned to Vietnam in 1992, spent another 12 years there and is the most decorated New Zealander in relation to Vietnam.

Enthralled, Sally filed away the Sr Sheila information, vowing to one day hunt her down. That day came later that year, after Sally’s daughter Trinity celebrated her 21st birthday.

“I thought Trinity had had a reasonably good life and I wanted to show her how other people lived,” says Sally. “I took her to India for a month and on the way back we called in to Vietnam to see if I could meet Sister Sheila O’Toole.”

Sally’s life path changed when “a lady, just about in rags” pulled up on a motorbike to meet this inquisitive fellow Kiwi. “She sat down and told us about her service at a leper colony. She’s the most amazing, bravest woman I’ve ever met.

“We sat there in the middle of nowhere in a street that was like another planet – so much poverty – and we were spellbound. She took us later to Ben San [Leprosy Centre], which was then run by nuns. It took about three-quarters of a day to get there from Ho Chi Minh. It’s walled, barbed-wired, and there were guards. I thought, ‘This challenge is a bit of me’ and that’s how it started.”

Sally went back to her Sunrise Rotary Club armed with the news that there was a lot of good they could do there, and got the desired support. An initial step was acquiring a licence so she could teach the nurses at the centre (none of whom were registered) how to look after leprosy patients. This was in the late 1990s and over the next 14 years, Sally visited voluntarily seven times for two-week stints of teaching and nursing. Nurses from other hospitals attended her lessons and she thinks she trained about 50 staff over the years. Sally left them her training manuals so they, in turn, could help others.

“It was very hands-on,” says Sally. “I’d help deal with the head lice, which were crawling; I’d massage lotion into the skin of those with scabies [previously they’d been scrubbed with pot mitts]; I’d go in at night and sit with the dying; and the nuns would teach me Vietnamese and I’d teach them English.

“The people there had so little. I used to take nail polish over and they treated it like absolute gold. They’d line up so I could paint one or two fingernails (that’s all they had) and they – women and men – loved it. The nails on every finger they had left would be painted a different colour.”

While there, Sally stayed at the colony in a bedroom where netting was a blessing as the spiders were “as big as dinner plates”. Initially, there was no hot running water, but Sunrise Rotary changed that by putting in solar heating. They also sent a container full of goodies including spare beds from the hospital she owned, Oakland Health. She also brought furniture, linen, games, felt pens and colouring books for the children at the school within the colony. Both contributions were life-altering.

Then there was the goodness that came from Comvita; namely, $149,000 worth of wound-care product. The healing effect that had on the leprosy patients blew Sally’s mind.

Sally’s missions to Vietnam continued until 2007. That same year she sold Oakland Health, having bought it 27 years earlier. Back then, it provided for 19 medical patients, mostly aged-care and a medical patients, mostly aged-care and a few young, severely disabled people. Under Sally’s watch, it grew to support more such patients, plus others with traumatic brain injuries, young patients, post-operative orthopaedic care and war veterans from Wellington, and offered aggressive and slow-stream rehabilitation and physiotherapy services, palliative care and a meals-on-wheels service. Apartments and a hydropool for rehab were added, which saw it catering for 102 people in-house and about 140 outpatients.

They were busy days, but there was always time for doing charitable good. Sally held governance positions at organisations such as Private Hospital Association and the Acorn Foundation. She helped start Tauranga’s first Lioness Club, the Tauranga Festival, and her precious Tauranga Sunrise Rotary Club, and judged competitions involving enterprising young people. The Queen’s people took note. “I got a gong,” smiles this New Zealand Order of Merit recipient.

Sally can’t park philanthropy. These days, she and some other women are part of a giving circle with the Acorn Foundation. “We put money in the can every month, then give it out,” she says, citing Women’s Refuge and disadvantaged children among the recipients.

She remains “neurotic” about New Zealand’s health system. It just doesn’t provide well enough for the many needs out there, she says.

Amid time with friends and family (her grandchildren live nearby) and beach walks with her two dogs, Sally is writing a book to inspire people to act on their dreams. “It’s not a look-at-me story,” she says. “It’s about how even if you come from nothing – I came from a state house – you can achieve whatever you like, with effort. My advice is to always surround yourself with a good team of supportive people. I couldn’t have done anything by myself – I owe whatever I’ve done to a team of people.

“Read about people with grunt, be a bit mouthy like me, and stick up for yourself and your basic principles,” is her advice.

Sally concedes she’s done good in her time but quickly adds that she doesn’t need awards, flowers, a red carpet or stories written about her. “If I get a smile, I’m as happy as a pig in mud.”

Honouring life with an exceptional commitment to care: Legacy Funerals’ Kiri Randall

“We’re not promised tomorrow, and we’re always faced with that in what we do. It makes me appreciate what I have in a different way.”

Tasked with the responsibility of honouring and celebrating life has given Legacy Funerals’ general manager Kiri Randall a whole new appreciation for hers.

INTERVIEW LISA SHEA / PHOTOS SALINA GALVAN

Kiri Randall faces grief every day of the week. Hers is a job full of big emotion; showing compassion, care and empathy for people in the midst of what might be some of the hardest days of their lives. It’s a lot to shoulder, but Kiri and her dedicated team are prepared to help carry that load, understanding personally how difficult loss can be. “We’ve had staff lose people in the last year that they never expected would have died before their time. So the reality is that it happens for us, too. We can relate so deeply to the people that come to us in that moment.”

Their commitment to care became even more meaningful last year, when COVID-19 restrictions impacted our ability to say goodbye.

“We did everything so that families were with their loved ones as long as possible. Once they came into our care, we made sure they had a proper farewell, we had someone say a committal; if the family prepared a eulogy, we read it on their behalf. We took video of the burial for the family so they could feel like they were part of it. It was an incredibly challenging time for everybody and we just wanted to help them through it as best we could.”

If that seems outside the traditional idea of a funeral, Kiri explains that today, traditional services are no longer the norm. Her team is guided entirely in what they do by the wishes of the deceased, their family members and friends. “Funerals don’t have to be limited to churches. We have them in our own venues, we have them in orchards, at the beach, at surf clubs; we’ve even had one on a barge. Whatever the person’s life was about, that’s what we want to reflect in the service. It can be in the morning, the evening, we can have their favourite foods served. We want it all to be individualised and a true celebration of their life.”

While funerals are as much about a moment to reflect and say goodbye for those loved ones left behind, Kiri says it’s as important to them to care for the deceased as much as the living. They have a team of qualified funeral directors, qualified embalmers and they’re committed to continuous training to ensure they offer a professional service at the highest standard. “It doesn’t mean we charge more than any other funeral home; it just means that we’re doing our very best, because that’s what we’re all about.”

For Kiri, it always comes back to truly honouring the lives of those that have passed; something she sees as a responsibility that has gifted her with a whole new perspective. “We’re not promised tomorrow, and we’re always faced with that in what we do, so it makes me appreciate what I have in a different way. I can appreciate as a mum that the best thing I can do is be an incredible mother to my children, to be there to support them in the good and the bad. For my staff, I want to focus on their health and wellbeing, to make sure they’ve got the tools and support they need to do what they do well.”

“It’s also made me appreciate my community. I’ve learnt that life isn’t perfect but I’m so blessed to have good people around me. I love having good conversations, with all kinds of people, from all walks of life. I want to learn from them. Ultimately, being in this line of work has really taught me to appreciate life.”

Ben Hurley finds the funny in cricket

“I made the Hawera High School First XI, but partly because one of my closest friends was the captain and put in a word. I’ve had my moments on the field but I was a bit of a late bloomer, physically, and by the time I was able to compete properly, other career paths had presented themselves. Mostly comedy and beer.”

Comedian Ben Hurley is bowled over by the “ridiculously quirky” game of cricket.

WORDS Ben Hurley

“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster,” is Ray Liotta’s infamous and chilling line in the opening scene of the Martin Scorsese movie Goodfellas. A story of a man born into the mafia; essentially a crime cult held together by family, centuries-old tradition, rival factions and unwritten rules and terminology that the uninitiated don’t really understand. I never wanted to be a gangster, but as far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a cricketer.

I know half of you stopped reading when you read that word. Cricket is an acquired taste, polarising like blue cheese or Jim Carrey. I don’t expect you to like it and understand if you don’t. I know it’s “slow” and “boring” and “complicated” and “sometimes it’s a draw after playing for five days.” I’ve heard it all a thousand times and it doesn’t offend me.

Cricket isn’t really what this is about. This column is really for anyone who thought their natural inability to do something (well) would preclude them from doing it for a living. Because I am one of that number and testament to the fact that it isn’t always the case.

I came to the game later than my friends. I grew up in an arty household more than a sporty one, so I never really saw much sport on TV. I remember New Zealand winning the 1987 Rugby World Cup, and a handful of moments from the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, but that’s about it. Until I was about 11 and a combination of cricket-mad next-door neighbours and seeing New Zealand play Australia in something called “The Benson and Hedges World Series” set off a strange reaction inside me. Something I’ve never truly been able to explain. Within a few months, I was part of a real cricket team that played on Saturday, and my bedroom walls were covered in posters of cricketers. I knew stats and names and nicknames and stats about nicknames. I’d caught the bug, with two hands, reverse cup, in front of my face.

Was I any good? Not really. But, if I’m honest, I wasn’t awful. I made the Hawera High School First XI, but partly because one of my closest friends was the captain and put in a word. I’ve had my moments on the field but I was a bit of a late bloomer, physically, and by the time I was able to compete properly, other career paths had presented themselves. Mostly Comedy and Beer.

I still played as a semi-social weekend warrior but the realisation eventually dawned on me that I was unlikely to make the premier club side, let alone the national one. I would always be someone who loved the game and could ruin any party by finding the one other cricket person in the room and settling in for the night. Commandeering a corner of the kitchen to loudly debate what went wrong in the 1992 World Cup semi-final loss to Pakistan. That would be my lot in cricket life. Or was it?

Around 10 years ago, when comedy and TV work became more abundant for me, New Zealand Cricket got wind of the fact that I was one of these cricket “tragics”, as we are often referred to (I prefer the term “nuffy”), and got in touch. They wanted something called a “Match Day Host” to travel around with the team over the summer and interview drunk people in the crowd for the big screen. Not only did I jump at this opportunity, but I did it for seven summers. Only giving it up and passing on the role to someone younger because I realised no one wants to see a 40-year-old man doing boat races on the embankment while a dozen Otago students chant, “Down in one!”

Once again, I thought that would be it for me but, last year, in a deal even more complicated than the LBW rule, Spark Sport got the rights to televise the cricket and they gave me my own show! Who said nothing good happened in 2020? And this is what I did all summer. Half-an-hour a week where I’m paid to talk about this game. This ridiculously quirky game that has featured in many of the happiest moments of my life. (My wedding, my kids’ births and Grant Elliot hitting that six at Eden park to put us into the World Cup final). It’s not a dream job because I rarely have dreams this good.

Ok, so I’m not a gangster, and yes, I still think about it. I didn’t have the genes or the constitution for it. But, in this analogy, maybe I’m Martin Scorsese, telling those who are interested all about the ones that do. And I’m mostly okay with that.

Deep + meaningful

On September 25, 2007, William Pike was caught in a lahar on the slopes of Mt Ruapehu. Less than 15 hours after the eruption, surgeons at Waikato Hospital were forced to amputate his severely damaged right leg below the knee.

WORDS MARY ANNE GILL / PHOTOS SUPPLIED

On September 25, 2007, William Pike was caught in a lahar on the slopes of Mt Ruapehu. Less than 15 hours after the eruption, surgeons at Waikato Hospital were forced to amputate his severely damaged right leg below the knee.

In the years since the accident, 33-year-old William, who lives on Auckland’s

North Shore, has returned several times to the mountain where he nearly lost his life. He’s also tramped, cycled, kayaked, climbed Antarctica’s Mt Scott, established nationwide youth-development programme the William Pike Challenge Award, and become a sought-after inspirational speaker.

But scuba diving, something he’d done extensively before his accident, was what he really craved. “It was the last thing I got back into post-accident, and it took nine years,” he says.

Whenever William tried to dive, the air inside his knee socket would be squeezed by the increasing water pressure, causing discomfort as he went deeper. “I tried lots of different ideas to prevent it, and finally using a silicone liner has worked,” he says.

That success means the former primary school teacher is now considering taking on more aquatic adventures. He recently went freediving at the Poor Knights Islands Marine Reserve off the east coast of Northland, but a much bigger trip – like his recent expedition on the HMNZS Canterbury with the Sir Peter Blake Trust to the Kermadec Islands –beckons.

After the accident, William was transported by ambulance to National Park, where Taupo’s Lion Foundation Rescue Helicopter was waiting to take him to Taumarunui Hospital. There, a team from Waikato Hospital, who’d flown in on the Westpac Waikato Air Ambulance, joined with the local hospital staff to stabilise him in the resuscitation room. Twenty-eight minutes later, he was off to Waikato Hospital, arriving nearly six hours after the eruption. His heart rate was 40 beats per minute, his blood pressure 65/29 and, alarmingly, his body temperature was 25°C, the lowest doctors at the hospital had ever witnessed in a living person.

William credits his fitness for his survival. “I’ve always been lucky that outdoor education, sport and hobbies were instilled in me from a young age, which ensured I was fit.”

Today, that’s not changed – and neither has his positive attitude. For William,

every day’s a good day. “Everyone sees the shiny side of people, but there were times when [losing my leg] was a nightmare,” he says. “Yet I got through the devastation. I was glad to be alive because I knew I shouldn’t have been.”

Setting himself goals while he recovered in hospital helped a lot. “I tested the boundaries,” he says. “The standard ACC leg was not what I wanted. The reality is, the Limb Centre decides what prosthetics you get depending on your [needs]; a Lamborghini is no good for a farm track, for example. To begin with, you get a stock- standard foot without much flex in it.”

Although gagging to return to his active lifestyle, William had to work towards it – and that started with adapting to life as an amputee. To give himself purpose and direction, he returned to the classroom within three months, then in 2009 established the William Pike Challenge Award – a personal-development programme for children in Years 7 to 9.

He doubts his life would have panned out the way it has had it not been for the accident. “I’d probably be teaching in a classroom and impacting on 30 kids a year, and now I’m impacting on 1000 kids or more a year.”

In 2014, William married Rebecca, a fellow school teacher, and the couple now has a daughter named Harriet. “I want to explore with Rebecca, run around with Harriet and take her on adventures, run a business, pay the mortgage,” he says. “We can all be explorers in our own world – whatever we do. If I didn’t have that explorer mindset, I’m not sure the challenge award would be what it is now.”

Happily, there’s no need for William to have any more operations, provided he’s careful, which he is. “During summer, it’s a battle because I always want to be out there doing stuff, but I sweat a lot in the [prosthetic] leg. I have to take it off and dry it, sometimes every 15 minutes, which really slows me down. At the same time, though, it gives me an opportunity to stop and think – a little like hitting the refresh button.”

William doesn’t consider himself disabled. “I’ve just got some challenges that makes things a bit more difficult. But I can do some things other people could never do. There’s always someone worse off than you.”

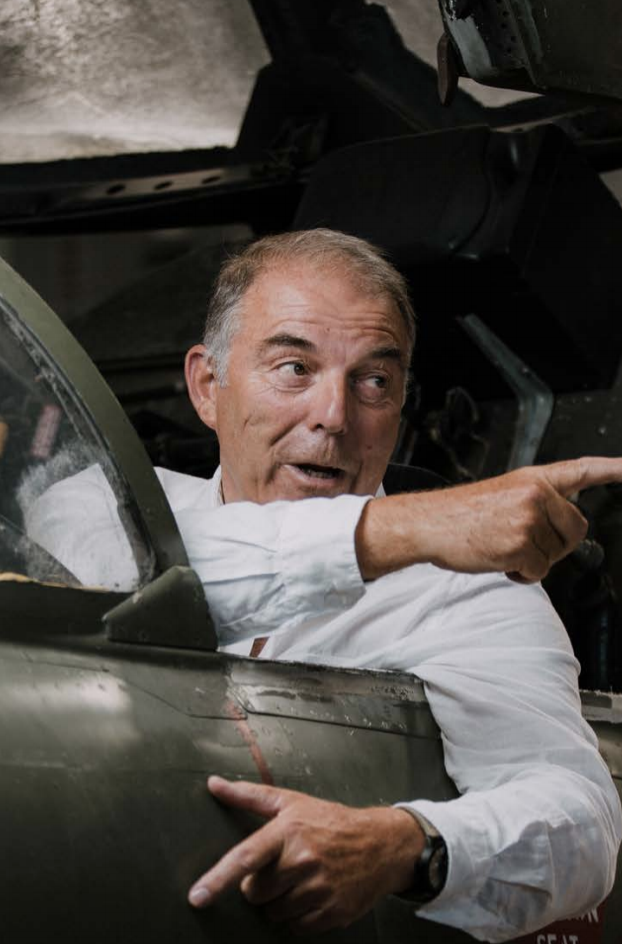

Serving in the Bosnian War

Stationed at the UN headquarters in Zagreb, I have many memories in that role. But one evening stands out in particular.

The Bosnian war involving the breakup of the former Yugoslavia in 1992 was a violent and bloody affair. The nations of the world under the banner of the United Nations decided to deploy humanitarian relief and armed forces to enforce a peaceful solution. I felt privileged to serve in this noble mission along with around 40,000 other people from many nations, including a good number from the New Zealand army.

New Zealand has a proud record of involvement, leadership and success in the realm of the United Nations. Helen Clark was the Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017 and was a candidate for the top job of Secretary General last year.

The whole United Nations show in The Bosnian War was lead by a very experienced, clever Japanese diplomat called Yasushi Akashi and the military chief was a short, fit, tough Frenchman called Lieutenant General Bernard Janvier who spoke little English, had a scar on his cheek, and had spent most of his life leading his legionnaires in active combat. I was proud to serve alongside him as his ‘Air General,’ arranging and advising on all matters of airpower and support, on behalf of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). The challenges were immense and there were some very dark times but, eventually, the conflict was suppressed and the warring factions came to a pretty much peaceful agreement which holds today.

Stationed at the UN headquarters in Zagreb, I have many memories in that role. But one evening stands out in particular.

I was the only non-Frenchman in a military tent on Mount Igman (home of the winter Olympics in 1984), overlooking war-wrecked Sarajevo. The other 30 or so were foreign legion officers, hosting a formal dinner in honour of General Janvier. It was bitterly cold, pitch black, and howling.

The evening started with great drama as the youngest officer smashed off the top of a bottle of champagne with a razor sharp sabre. After the meal the officers sang mournful songs about comrades who had died in combat and they also sang about women, both real and imaginary, loved and long lost. Later Janvier gave a short speech and said of the singing, "tous les chansons des soldats sont tristes." (all soldiers’ songs are sad). I told him later that should be the title of his memoirs. The evening was moving, eerie, and beautiful.

I have worked in the military and later as a businessman in multinational organisations. It carries much in the way of frustration, challenge and, to a degree, inefficiency, when compared to single nation institutions. But I can say with conviction that working with others on big challenges in the end produces better, more durable and more satisfying outcomes. The big portion of my teenage life growing up in New Zealand taught me that the ability to work with other cultures is very much part of the Kiwi values and skill set. And I am grateful to have acquired it in this great country.

Marine kayaking starter pack

“The ocean is my go-to place for clearing thoughts, working out, and allowing the positive ions to completely saturate me and enhance my general well-being. I always come off the water smiling from ear to ear.”

Kayaking is a way of life for our favourite marine life expert, Nathan Pettigrew.

The ocean is my go-to place for clearing thoughts, working out, and allowing the positive ions to completely saturate me and enhance my general well-being. I always come off the water smiling from ear to ear. Seeing sharks, orcas and seals are just a bonus.

Here’s how to get involved.

Cover up! The right clothing is a must. On a hot day, I wear a thin, long sleeve UV-resistant top which allows wind to pass easily through the fibres for cool, unrestricted paddling. A hat and sunglasses are also essential as is a good dose of sunscreen. On cold wintery days, I layer up with a merino shirt underneath a windproof kayak jacket. Gloves are handy too for warmth. But there’s one piece of kit you must invest in and wear at all times: a personal flotation device (FPD). I would never go out without one. If things turned bad, it would be the one thing which brings you home.

Fuel up! For short trips around the harbour, I take snacks and water. For longer trips I often take a cooker and meals that are prepacked in sealed bags. I’ve been known to throw a nice piece of steak and some potatoes in a cooler bag and enjoyed a nice fry up on a quiet beach somewhere after a long morning of paddling! On multi-day trips, I take food packed with protein and energy, but it's imperative for any kayaking session, no matter how short or long, to take a lot of water. Your body will quickly shut down without it.

Safety first! Before you venture out for the first time, skill-up. Find out how to deal with different scenarios should things turn bad. How do you get back in a kayak? Practice your technique until it becomes habit. There are kayaking clubs around to help with this sort of thing. Invest in an EPIRB (electronic positioning indicating radio beacon). If need be, you simply push a button and the coastguard will come to your exact location. I take a VHF radio and GPS too. Paddle floats and pumps are other key items too because, quite simply, your life is worth the investment.

At the ready! I need my essentials to be within easy grasp. My kayak has two large storage hatches and two smaller, day hatches for water, snacks and camera gear. The bigger hatches are used for cooking equipment, a tent for multi-day trips, sleeping bags and food. It is quite surprising when packed correctly, just how much you can cram into a kayak! In the bigger hatches, everything should be put in a dry bag to protect your gear from water, and any rubbing that may occur.

Snap it! Use a waterproof camera or a camera with housing to prevent it from being destroyed by saltwater. Small action cameras are great, but some take wide-angle photos and offer no zoom function, so subjects can look further away than they really are. Smartphones take incredible photos and offer a pretty good zoom. This helps if you are near marine life that you can’t get too close to (make sure you research all the DOC rules and regs to protect our marine life). Take your time, keep the horizon straight, and learn about light and how it affects your shot. Lock your arms on your kayak like a tripod, for a steadier shot.

Finally...

Kayaking has changed my life. I now work with people and organisations beyond my wildest dreams (like UNO. Magazine!!). I can’t stress enough the safety knowledge required for being on the water but once you have gained enough skills, get out and utilise our beautiful ocean and waterways and get back in touch with nature. I doubt you'll regret it. If you have any questions, or I can help in any way, get in contact with me on Facebook. Be good to the ocean!

The Don

“As a barber you become an instant counselor. I’ve been doing this for twelve years now and I know how to get people to talk. The barbershop encourages conversation. It actually helps a lot of guys to relax.”

WORDS TALIA WALDEGRAVE PHOTOS JORDAN VICKERS

“I lost seven friends in four years. That’s not okay.” Fighting the war on suicide, Sam Dowdall is embarking on a quest to raise awareness for mental health, specifically for men.

Snipping locks in homes from Matua to Matapihi, Sam Don Barber has become somewhat of a local icon. He is smart, eloquent, and incredibly personable and as far as cool hairdressers go, none of them quite compare to his dapper effervescence. Dropping cheeky innuendos throughout our chat, he tells me about his upcoming pilgrimage from north to south, trading haircuts for goods and services.

“I got over waiting for the weekly paycheck and doing everything for myself, so I made a decision to help others. I love the feeling I get from it, I get a heart on, or an affection erection.”

SHAKING OFF THE STIGMA

“People hear the mention of mental health and instantly think of a straight jacket, but it’s time to break down those perceptions. There is a bad attitude amongst younger men, especially when you hit the provinces, so I’ll be focusing on rural, coastal and lower socio economic areas.”

“The problem comes from a mix between mental health and emotional illiteracy; what you might be suffering from, teamed with being too scared to talk about it. That’s what this is journey is all about. Encouraging people, especially men, to speak up and communicate. It’s about knowing how to put your hand up and ask for help.”

His plight is one I encourage. Most New Zealanders are affected in some way by mental health or suicide, yet the taboo surrounding it leaves us sitting in an eerie and ignorant silence.

“As a barber you become an instant counselor. I’ve been doing this for twelve years now and I know how to get people to talk. Often when someone is dealing with an issue, it tends to stem from fear and frustration, but the barbershop encourages conversation. It actually helps a lot of guys to relax.”

“Touching another man’s face is something many men are not accustomed to, but it’s extraordinary to watch what happens. First there’s a long silence, but it only takes a moment before they open up and share something really personal.”

It’s this fire in the belly teamed with an empathetic understanding that will aid Sam on his top to toe sojourn. It helps too that he has the gift of the gab.

ONE HECK OF A ROAD TRIP

According to Sam’s calculations, his trip will take precisely 680 days.

“I’m building the caravan at the moment, one piece at a time. I take donations for haircuts and then I use that money to pay for materials. If I get 20 dollars for a cut, I can use that to buy a piece of plywood construction.”

“This isn’t about making money. All I need is just get enough to feed me and the dog and anything we don’t use will be sent to my major partner TradeMe. 100 percent of the profit made will go straight to Lifeline and anything we don’t eat to the local Food Bank or SPCA.”

The main focus will be on small New Zealand towns and in particular, volunteer firefighters; the first port of call when crisis arises.

“Some of these guys see up to seven or eight suicides a year. That’s a big chunk of their community. I want to work with them to teach others how to manage a crisis.”

Sam will also train local hairdressers and barbers at no cost, on the proviso they’re on board with the project.

“I really want it to hit home just how important it is to give back to the community.”

“I’ve wanted to do this for a while and tried a few years back, but I didn’t have the right planning behind me. Yes, there’s a lot of admin involved, but I love it and I actually find it very, very easy! I think the most intense part for me will be the traveling and constant time on the road.”

EMBRACE VULNERABILITY

“If you’re ever worried about someone, the best way forward is doing something together. Get out, go fishing, surfing or hunting but make sure you stop and ask, ‘Hey mate, are you alright?”

“It’s so small, so incredibly minute, but that there, that one question can make all the difference, and there’s something really special when two blokes are cut from the same tree and share that level of vulnerability.”

Teetering on the brink of suicide is an incredibly dark place to be, and it’s often difficult to imagine the possibility of a future.

“I’ve helped people in this situation and I want to educate others on how to do the same. It’s about sitting down and saying, ‘Let’s have a listen to what got you here. What’s going on? What steps can we take to make sure you’re safe for now? Let’s make a plan. I can’t fix you, but I can make you safe for now.”

Because it’s there to be done

We launched just after sunrise with an outgoing tide, passed Rangitoto island and headed out to the open.

WORDS NATHAN PETTIGREW

This summer I met Brent Bourgeois, a well known Mount local and we discovered a shared passion for the environment. He had an idea to SUP (stand-up paddle board) from Auckland to Tauranga and asked if I wanted to come as support crew. Thinking it was 'just a bit of talk', I said "Yeah, for sure." Brent tagged me on Facebook and announced the paddle, and I thought "oh hell!" It was on. The set date: February 23rd. The reason: Because it was there to be done

Day One 65 km:

My upper body was ready, but sitting for so long was going to hurt. We launched just after sunrise with an outgoing tide, passed Rangitoto island and headed out to the open. I was excited about the marine life, and The Hauraki Gulf did not disappoint. Tailed by Mako sharks and dolphins that put on a spectacular show were highlights. The conditions were silky calm, right up until about 8 km from landing when the wind picked up. Brent’s focus and strength saw him through to the end, though. We landed at Port Jackson to enjoy a stunning sunset over a barbeque.

65kms.

Day Two 57 km:

Today we really had to watch out for each other, as rounding the point at the top of the Coromandel was not for the faint-hearted. The swell was around two metres and with confused water coming at all angles, it was one of the scariest moments of my kayaking career. We got through the worst of it to be faced with dark clouds that rolled in fast. The heavens opened and hammered down on us. We were then confronted by a head wind and were quickly running out of time to land. I sat in the kayak for a total of 12 hours solid. And it hurt. Big time. We finally arrived at Opito bay and I was very happy to fall out of the kayak and onto dry land.

Day Three 60 km:

I spent last night in a cabin, not my tent, so a good bed helped to ease my aching and broken body. We set off on yet another pearler of a day with a plan to stop at Hahei for coffee then on to our destination at Whangamata. It was all plain sailing until around five km out when a head wind picked up and made for a slow trip in. We powered up with electrolytes and bars to keep us fuelled during these last few kilometres so we were 'all smiles' as we rounded the point to come in for landing. That was, until I saw the surf. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a huge fan of kayak surfing, but not when I’m in a sea kayak with gear onboard and cameras out in the open!

Day Four: 61km

My wet shirt made for a slightly uncomfortable start, but it didn’t matter as the surf was still pumping as we walked towards the glowing sunrise. I opted for powering through rather than timing the sets and it was a refreshing way to wake up. At the southern end of Whangamata, we could just see The Mount! The adrenaline was pumping and we went for it. After a quick stop for coffee in Waihi beach, we were ready to tackle anything, even the Bowentown Bar which was just rockin' and made for some fun surfing. Past 20 km of Matakana island, Mauao was like a welcoming giant standing above us. Emotions started to flow. I had close friends around The Mount waving and cheering and the old eyes were definitely watering. As we drew closer to Pilot Bay, we were met with applause. It took some doing, but we had done it!

Life is short. Don't let it slip by.

Food is the answer

Cook, author, and actor Sam Mannering dusts off his pen and paper and starts writing invitations.

Cook, author and actor Sam Mannering dusts off his pen and paper and starts writing invitations.

I have so many friends within walking distance of my house. Some of them I barely see twice a year. I’ve always felt bad about that sort of thing. We only ever get together at some forced event, and horribly enough, it always seems to be funerals. Even weddings don’t get people together. I’ve been to far too many where everyone stands around afterwards in the same haze of realisation as someone blurts out that we all must start catching up more often. It never happens. We get too caught up with the littlenesses, the trivial.

I’ve decided that food is the answer. It always has been.

I often find myself drawn to cultures who have been through more than their fair share of strife, because it’s there you’ll see the most love. And it’s always expressed through food. I think of places like China, the Middle East, Vietnam; cradles of conflict and oppression for thousands of years; and yet the people are always so generous, their cuisines so powerful, so important to their way of life. Cooking is love; no matter what, whether you are sitting around a pot in a bomb shelter or hiding out in the jungle it means that you get to be fed soon and that you will make it through another day; it means that for a few brief moments everyone is safe, contented, together.

I’ve recently discovered Chef’s Table on Netflix. I generally cotton on to popular culture approximately two years after everybody else. One episode features Jeong Kwan, a South Korean monk whose simple vegetarian food has blown the minds of the global culinary elite, from Eric Ripert to the New York Times. What drives the beautiful essence is her unselfishness, her generosity. A separation from ego; a simple desire to do good through food. And it is as much the attitude itself that makes her work so stunning.

We’re too damn lucky here, but it seems to be pushing us apart. I don’t want to sound to tediously pious here but food should be bringing us together. I’ve realised that being a chef should make me a bit of a torchbearer. I can’t think of a better way to express generosity and love than through food.

Where am I going with this?

We don’t have much to complain about here. Things seem all a bit grim elsewhere at the moment what with maniacal toupees and xenophobia on the rise as if the twentieth century never happened. Others dribble on about Finland or Denmark being so wonderful but then again who wants to have Putin breathing down your neck at the promise of some nice new lebensraum. We do pretty well down here in our little corner of the Pacific; perhaps going that little extra mile to make more of an effort isn’t quite so hard after all.

I’m going to start inviting my friends around for dinner more. And you should too. I’m getting tired of the ‘oh we must catch up’ and then ten years go by and we’re at a funeral.

It probably won’t make you as zen as Jeong Kwan, but it’ll remind you how lucky we are.

Back to work

UNO’s new columnist might be a comedy big shot, but he’s not immune to that first-week-back-at-work feeling, from which he’s still recovering.

UNO’s new columnist might be a comedy big shot, but he’s not immune to that first-week-back-at-work feeling, from which he’s still recovering.

PHOTOS BRYDIE THOMPSON

No one really clocks on mentally until after Waitangi Day. Sure, your body is at work but your mind is not – it’s still riding those breakers at Papamoa, drinking cocktails for morning tea, or avoiding a flying Virat Kohli six at the Bay Oval. It’s just too bloody hot, and we’re still digesting the 4kg of ham we ate over Christmas.

It’s a wonderful time of year, and it’s also very frustrating. Trying to enlist the services of a tradesperson during January is a fruitless exercise. They know full well that you have money to give them in exchange for their services, but who needs money when you have sunshine and cold beer? They’ll get to you, but not till at least February 7.

The television shows I work on take a break over summer as well. 7 Days does about 40 episodes a year but thankfully is off air during the time when all the news cycle seems to consist of is record temperatures and the odd shark sighting. However, The Project comes back a little earlier – and it was its return that knocked me out of my hammock.

I’ve been contributing to The Project since it started in early 2017. I fill in on the panel sometimes when Jeremy Corbett is away and recently they’ve asked me to do some interviews with some big names in music. It’s not overstating it to say that this is a dream job for me, an ageing Taranaki-bred bogan whose hearing is missing a few frequencies, due to listening to Nirvana and AC/DC at louder than recommended volumes in my mum’s 1989 Ford Laser back in the day.

So far, my interviewees have included Weezer, Queens of the Stone Age, Cat Stevens, Tom Morello of Rage Against The Machine and Corey Taylor of Slipknot, so when my producer emailed to ask if I’d interview my favourite guitarist, Slash, I ignored the fact that it was January 24, well shy of my official Waitangi Day work kick-off, and shook myself awake.

Saul Hudson, aka Slash, the iconic lead guitarist from Guns N’ Roses, all top hat and black curls, was to play two shows in Tauranga and Auckland with his new band Myles Kennedy & the Conspirators and had agreed to his first television interview in five years. With me. I still have no idea why.

So, first day back at work in 2019, and I’m in a lift heading up to the penthouse at Auckland’s Pullman hotel. I was feeling the pressure; idol worship aside, Slash doesn’t really ‘do’ interviews because he’s shy and all anyone asks him about is why Guns N’ Roses broke up, which he’s sick of talking about. His record label told me not to ask him anything about Guns N’ Roses or Axl Rose or Duff the bass player or Steven the drummer or the November Rain video or the ’80s or firearms or flowers of any sort. This directive came by email but was reinforced in person by his very friendly but very large, 7ft-tall head of security just before Slash came into the room. Point taken, giant security man – point taken.

Slash sat down and got out some nicotine gum. I broke the ice talking about smoking, how hard it is to quit and stay quit. He relaxed a bit as we quietly chatted about the different methods of giving up ciggies. It was a bit weird as I’ve never smoked, but I needed a way to start talking without launching into the meat of the interview. I lied, just a little, and I feel medium-bad about this.

The standard time frame for these interviews is 15 minutes, but Slash gave me 20 and I can say he’s as pleasant a man as I’ve met. For someone who’s notoriously suspicious of the media, he was generous and friendly, and I think I even made him laugh a couple of times. We covered his childhood growing up in Los Angeles, his hippy parents, how he lived on the same street as Frank Zappa and Joni Mitchell, his love of reptiles and all the usual rock ’n’ roll stuff about touring and albums and crowds and fans. And guess what? He mentioned Guns N’ Roses, like, four times.

Then he left, and I drove home, adrenaline still coursing through my bogan veins. I felt a mixture of disbelief and relieved exhaustion. The next day was the start of anniversary weekend. Thank god – I needed a few days off.

Father + Son: Tim and Finn Rainger

Both freelance writers, father and son team Tim and Finn Rainger talk about their relationship.

Both freelance writers, father and son team Tim and Finn Rainger talk about their relationship.

FINN RAINGER: SON ON FATHER

My Dad, or Munter as I more frequently call him, is far from your average human being. He’s a self-described outsider with an affinity for the strange. Surfing, he reckons, brought purpose into his life as an alienated and vexed youth. The memory of my first proper wave, aged 16, at Taupo Bay with him hooting from the beach, drifts into my consciousness every so often. “No wife, no career, no mortgage – it is not a lifestyle that many live, and thank fuck for that,” he stated during lunch recently. I admire his resolve in pursuing a lifestyle that suits him.

This year I indulged our shared obsession for chasing waves by joining him for the season in Indonesia, where he has spent the last four years away from the New Zealand winter. We have many similarities: a psychotic tendency to twirl strands of our hair when concentrating, and a passion for reading, writing, and taking photos. One of my earliest memories is sitting in the passenger seat of his van in Cornwall, England, probably on the way home from the beach, with Sublime playing loudly and smoke billowing out the window.

Like the surf, Dad can be fickle and stubborn, and hard to contact, but when you do have his attention he usually brings something to the table, whether it’s a plan, story idea, or advice on the age-old question of what is the point? He is adept at putting life into perspective, and it was his advice combined with my Mum’s that convinced me to take a job working as a reporter for the Gisborne Herald in 2015.

His capacity to impart advice and wisdom to people who want to hear it, as well as those who do not, earned him the nickname “The Sheriff” from the Canngu, Bali, locals. He patrols the line-up in the water, always on the lookout for a snake (someone who commits the cardinal sin of paddling inside other surfers and not waiting their turn for a wave), and does not shy from the confrontation that ensues (never violent in my experience).

The nickname is applicable on land, as he has a sharp moral compass that he willingly extends beyond his own periphery. A group of European “hipsters,” as he labelled them, were drinking and listening to dodgy music at around 10pm at our homestay in Canngu and around 10pm at our homestay in Canngu and Dad, wanting to sleep, got out of bed with a grim smile on his face and headed over to sort them out. “This is a homestay. There are plenty of places to party in Canngu without keeping me awake. Live and let live!” They were not happy and got a few digs in, “This is what happens in Canngu now. It’s not the 70s anymore old man.” But he had a point, and they vacated the premises soon after, honking the horns on their scooters as they hooned down the driveway.

All those hours spent battling his two brothers at home, and bullies at Auckland’s Kings College have toughened his edges and he can be an intimidating, yet compelling character. Dad’s a softy at heart though, and has a tender spot for the underdogs of life. A couple of German girls recently told him that if he were to write a story on his life, they would read it. Me too - if I hadn’t heard most of it already.

TIM RAINGER: FATHER ON SON

To commit to print my thoughts and feelings for my son is hard. Relationships are so fluid and print is pretty final. Every word scrutinised for each subtle nuance. Plus I’m sharing a room with him as I write this; we have been for eight weeks. Surfing together every day, eating, drinking, hanging out. There is no luxury of distance. But here we go.

Let’s start with the bigger picture. We are more like an older and a younger brother than most fathers and sons. Most of the time. There are obviously moments when I have to lay down an ultimatum but they’re pretty rare. Ever since he did a milk-puke down a cold Kronenberg I was drinking (without me noticing), and which I subsequently gagged on, I’ve cut him a bit of slack. He’s always been quite determined to do stuff by himself, and certainly never wanted my advice.

When he was about two, his mum was on the phone so he flipped over a bucket, got up on the bench and merrily began chopping potatoes, which apparently was going fine until it wasn’t. By the time I got there to take him to hospital, there was blood sprayed all round the kitchen walls. He’s very close to his mum and his young brother, as well as his step-dad and all their extended family. There is a sixteen-year age gap between him and his little bro, and it’s funny observing how their patterns of behaviour mirror ours. At times he parents him hard, and others they josh around and have lots of fun.

He’s always loved reading and music, and especially loved being read to as a kid. “One more story dad!” was a line I heard a lot. It’s a great pleasure now, sharing books and bands, picking the guts out of movies and so on.

We’ve done a lot of surfing together since the beginning and it’s been a great thing for our relationship. Setting the clock. Getting up in the dark. Trading waves. It’s our mutual happy place. It’s our second season in Indo; this time we’re here for 6 months, and that’s a lot of time living cheek by jowl.

A few people raise their eyebrows when we tell them what we’re up to, like I’m being irresponsible letting my kid quit his job and spend all his savings on a surf trip. My take is: well, he’s qualified, and he works for his own dough, saving for a year to get here. And now he’s really focused on surfing hard, doing yoga, eating well. This is an experience that will shape him physically and mentally in really positive ways, and is one he’ll never forget.

He’s a good kid. I’m proud of him. And I like hanging out with him. Most of the time.