Reel Ambition

The unstoppable Bryce Dinneen from Wish4Fish proves there are no limits to sharing his adventurous dreams.

The unstoppable Bryce Dinneen from Wish4Fish proves there are no limits to sharing his adventurous dreams.

WORDS Sue Hoffart

PHOTOS Graeme Murray + Logan Davey + Supplied

Four percent. According to specialists, that’s the level of voluntary movement Bryce Dinneen has retained since his mobility was snatched by a single dumb, drunken dive into Wellington Harbour.

He jokes that, statistically speaking, he now has to work 25 times harder than other people just to keep up.

In fact, the Pyes Pa resident has been outrunning the able-bodied for years, with his clear-headed vision, outstanding fundraising feats and extraordinary drive to share the joy of a salt water adventure.

Bryce formed a trust and launched the Wish4Fish charity a decade ago, to smash down the barriers that prevent some people from boating and fishing on the ocean. Under his watch, the trust has spent almost $90,000 taking more than 350 people onto the water regardless of their physical or mental disabilities, illness or financial needs.

But he’s always had bigger fish to fry.

Hiring less-than-ideal vessels to take groups of two or three people at a time only proved to him that demand greatly exceeded capacity. So Bryce has driven an additional fundraising campaign that has raised $2.4 million. This venture, dubbed Project Noah, funded the design and construction of a remarkable custom-made boat that has opened seagoing doors for even more people who would otherwise be confined to land. First launched from Tauranga Bridge Marina recently, the world-first 18m vessel caters for 1000 people a year.

Last year, he was named volunteer of the year in the TECT Trust community awards for being “a shining example to us all to never give up, and to strive to make the world a better place.”

And he has pulled all this off with 96 percent less mobility than most of the rest of us; a shoulder shrug on the left side, some movement in his right shoulder and bicep. It’s enough to manipulate the phone he keeps in his lap and operate his motorised wheelchair, not enough to scratch his nose. His ever-whirring brain works overtime, though, alongside an uncanny ability to articulate and quietly inspire.

It’s been a team effort, of course. Bryce is adamant credit be given to all the family, friends, trustees, management team and generous business people, strangers, tradespeople and major funders who continue to work alongside him. However, there is no doubt whose audacious dream they’re following.

“Fishing’s part of it,” the charity founder says, explaining his determination to build a large, stable catamaran fitted with everything from hospital beds and a ceiling hoist to an accessible bathroom, shower, elevator and modified fishing rods. “But sometimes it’s not about the fish. It’s about the camaraderie, the highs and lows, losing a fish then trying again, channelling that frustration in the right way. It’s about getting out on the water, wind in the hair, sun on the face. It’s about normality.

“If you have an illness or a disability or a hardship, if your life’s frazzled, you can spend a day on the water and I guarantee you’ll come back with some kind of clarity.”

He describes seeing people with serious diagnoses – schizophrenia, bipolar, cancer, tetraplegic – leave their worries on land when they embark on a Wish4fish voyage. Accompanying caregivers, often overextended family members, are similarly uplifted. Some passengers have never been on a boat, others are keen fishers who imagined they would never venture on one again.

Bryce feared he was in the latter camp for much of his 11-month stay at Burwood Spinal Unit, following his life-altering accident.

He tosses out more numbers from those difficult days in the Christchurch hospital. Like 8kg. That’s the weight that was initially attached to his head back in 2007, when he spent 23.5 hours a day in head traction to stabilise the fractures that had caused paralysis from the neck down.

He was at a stag party in Wellington when it happened, an outgoing, carefree business student dressed in a suit and tie. Bryce and a dozen friends started the day with a champagne breakfast – “too much champagne, not enough breakfast” – and decided to leap into the harbour to sober up but he misjudged the depth of the water.

His neck was broken and his spinal cord so badly squashed, doctors likened it to the damage caused by an elephant standing on a tomato.

Until then, he was a fishing-mad 29-year-old cheerfully on the verge of a new career. Having abandoned a building apprenticeship, he spent 10 years immersed in the “bright lights and late nights” of the hospitality industry before launching into an Otago University finance degree at age 28. He’s always been entrepreneurial and still can’t drive past a kid selling something on the roadside without making a purchase, even if he has to toss the bagged fruit or homemade lemonade away. In his teens, the former Tauranga Boys’ College prefect was a top cricketer who hoped to play for New Zealand. He also chaired the school’s charity committee, gathering skills he never imagined using from a wheelchair.

Suddenly, he faced the prospect of never walking, never feeding himself.

“Mum and Dad brought me up the right way, to open the door for a lady, to pull the chair out for her, to give someone else that seat on the bus. I want to kick a soccer or rugby ball around with my two nephews. Those options aren’t available any more.

“Now, I need someone to turn the light switch on in the morning and to turn it off again at night and everything in between.”

He describes one grim day of hopelessness in the early months and recalls how horribly upset this attitude made his parents and sister.

“I made a promise to myself. No more tears. Whatever happens moving forward, I’ll try and make the most out of it.

“Mum and Dad are really good people. They worked hard, they provided for me but they also taught me you have to work a little if you want to get a little.”

So he focussed on what he wanted, rather than what he couldn’t do. Like getting back on a boat and fishing again. Or using his voice to advocate for others, especially those with disabilities.

It was the photos stuck to the ceiling above his hospital bed that inspired him; images of happy times in the company of good people and plenty of fish.

“I was like, ‘how am I going to do this again’,” Bryce remembers of his determination to return to the sport he has loved since dangling a line off a wharf at age four. “Speaking with people on the spinal unit, fellow patients, I’d ask ‘would you like to go fishing’. I used to hear ‘never’ a lot. And ‘can’t’. When you’re someone with a disability you hear ‘never’ and ‘can’t’.

“Those words are still there in my vocab, they just get flipped around. If you say negative, I say challenge. You can change so many things.

“There’s stuff I have to manage that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy, but I’m grateful. I just appreciate everything, waking up every morning. Every minute is just gold for me now. Me getting up in the morning, that’s gold. And if it’s not, well, sometimes you need a day in bed.”

He was still undergoing rehabilitation, living at home in Tauranga with his parents, when he established Wish4Fish. A local accountant and a lawyer helped establish the trust that would govern the charity, serving as unpaid trustees. Initially, they needed to raise money and profile amidst a sea of 27,000 other registered charitable New Zealand trusts, churning out funding applications and talking to people in the community. The team has expanded since then – Wish4Fish has a general manager – but Bryce has lost count of the number of fundraising sausage sizzles, dinners and corporate events he has personally attended. Or the talks given to service groups and interested companies.

Bryce fundraised $2.4m over 10 years to build FV Wish4Fish.

From the outset, it proved difficult to find a suitable, wheelchair-friendly boat for the charity trips. Charter boat skippers were nervous of tackling the necessary logistics and most vessels proved unsafe, too unstable, with difficult access and problematic layouts. Often, Bryce would test potential vessels himself to see what possible issues that others might face on board. He even submitted to the indignity of being hoisted out of his chair and lifted over the side of a boat when his wheelchair would not fit.

“First, you’ve got to get onto the boat from the dock and you don’t want to be faced with stairs to access the bathroom. Then you have someone in a wheelchair, on a moving platform. Having a high level spinal cord injury, I can’t regulate my body temperature and you’re dealing with sea conditions and weather that can change at any time. If people are strapped into a chair and they go overboard, they’re going straight to the bottom so everyone wears an auto-inflating life jacket. There are a whole lot of health and safety issues.”

Boat owners tried to help. One commercial skipper offered to widen the back of his boat and built a ramp to get Bryce on board. Monohull boats were deemed too unsteady. Most were too small to take more than two or three high-needs people with their caregivers. A boat owned by a double-amputee in Coromandel proved better than most but every vessel required compromise.

“The only solution was to build a boat,” he says, comparing his ‘build it and they will come’ philosophy to Noah and his ark.

As the catamaran nears completion, he and the Project Noah team are focussed on the next stage. That means creating a sustainable non-profit organisation that can fund ongoing operational costs – paying a skipper, maintaining the boat, taking passengers at no charge - by hiring the boat to corporate, community and educational entities.

Support continues to come from multiple quarters, like the occupational therapists working at local medical equipment firm Cubro. Or the companies that have seized on the cause and run their own fundraising events. Currently, he is in discussion with staff from Waikato University’s marine studies department, to find ways to work together.

He credits UNO magazine with significantly raising the charity’s profile when it published his story back in 2016. That led to an offer of help from a reader with project management and feasibility study skills, which in turn set Wish4Fish on the path to winning a game-changing $1.5m New Zealand Lottery grant.

In 2016, television personality Matt Watson showcased the charity and its founder on screen. When Tauranga retiree Ray Lowe saw the show, he stepped forward to design a fishing rod that allows Bryce to cast and wind in a fish independently, courtesy of electric reels and technological wizardry operated from an iPad in his lap. The inventive stainless steel specialist has gone on to build and donate more of these fishing rods to others and to help with other public accessibility projects.

Bryce credits his friend with driving the Wish4Fish boat project forward, too.

“Ray’s a special kind of guy. He’s a lot more determined than me, with a 24-carat heart of gold. One day, he said ‘Bryce, if you want to build a boat let’s go draw it, map it out. So we went on an asphalt area and just mapped it out with chalk. Then we came back and measured it out. It was me and a guy and some chalk in a carpark.

“He was the one who said we need to make the wheelchair or disability king or queen on that boat, make sure all the sharp edges are smooth. Add extra beds for the support people who stay overnight. It needs to be truly accessible to all.”

Bryce pauses and smiles, staring into the distance.

“Imagine if the family of someone with terminal cancer has the ability to go out to Mayor Island on that boat and see the sunrise at Southeast Bay before their life gets really tricky.”

Once the catamaran is in the water, he plans to step back from the “boat of joy” project that has consumed much of his energy in the last decade. It’s not his boat, he insists. It belongs to New Zealand.

After the launch, he will spend more time with his beloved family in Christchurch, seek employment, fish, watch some cricket and relish seeing friends without tapping them on the shoulder to buy tickets to a fundraising event. That said, he can’t help imagining the changes he might be able to make for disabled people who have to negotiate airline travel.

In the meantime, there is more grassroots work to do for the man who conjured a multi-million dollar dream then made it come true. Tomorrow, he has people to meet and sizzling sausages to sell at a corporate fishing competition.

Olympic and Commonwealth Games heptathlete Sarah Cowley Ross carves out a new career

To reach the standard required to represent your country as an Olympic and Commonwealth Games athlete is extraordinary. To reach that standard across multiple disciplines is, in my view, verging on superhuman.

WORDS Nicky Adams PHOTOS Graeme Murray + Supplied

The Olympic and Commonwealth Games heptathlete’s journey to redefine herself is about leaning hard into her core values and carving out a career where sport still takes the centre stage.

To reach the standard required to represent your country as an Olympic and Commonwealth Games athlete is extraordinary. To reach that standard across multiple disciplines is, in my view, verging on superhuman. To be so talented, disciplined and dedicated, and still be a well-balanced, grounded and thoroughly lovely person – surely that’s impossible? Apparently not.

Aotearoa heptathlete Sarah Cowley Ross is all of the above and more. If you’re a little hazy as to what a heptathlon actually involves, to clarify, it’s a combination of track and field events that requires both speed and power. Over a period of two days, athletes compete in a total of seven events: A 200m and 800m run, the 100m hurdles, and the high jump, long jump, shot put and javelin. Heptathletes are given points for their best performance in each, then ranked according to the highest overall score.

Sarah competed in the heptathlon event at the London 2012 Olympics, where she placed 26th out of 38, having previously placed 10th out of 12 at the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne. At the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, she narrowed it down to the high jump, placing ninth out of 24. Although these are the events that have garnered her the most attention, they’re only the pinnacle of myriad incredible achievements during the course of her career.

I’d presumed the world-class athlete would be a certain type of person, perhaps buzzing with pent-up energy. In fact, I found her to be warm, relaxed and only identifiable as an athlete by her long, lithe legs and an aura of fitness I sometimes fantasise about possessing myself. So deceptive is her demeanour, it’s hard to imagine her out on the field, mentally slaying her opponents one by one.

With a smile, Sarah tells me, “A lot of times people have said, ‘You’re too nice to win – you’ve got to be more mongrel.’ But I can turn it on and off when I need to. I’m very competitive. I always want to win, but that’s changed in the sense that I’m quite comfortable with who I am, so I don’t need to win Pictionary every time! I’ve also changed in that now I want to win for the collective – for communities.”

Sarah was born and raised in Rotorua; her mother Robyn Cowley is New Zealand European and her father Jerry Cowley moved to New Zealand from Samoa when he was seven. Sport was always an integral part of family life; Jerry (who sadly passed away when Sarah was 19) represented New Zealand in basketball, and her brothers Garrick and Richard are also blessed with more than their fair share of sporting prowess. Sarah says that when they were children, there was an expectation that they incorporate sport into their daily life, but not at the expense of other things.

“Looking back, we were allowed to be kids, and play was a big part of our lives. I was just fortunate that I had brothers who were better than me physically and who unconsciously pushed me. I was just always trying to keep up. Later, they’d join in my training sessions. My brothers are two of my closest friends, and when I reflect on my journey, it’s been a family one.”

By the time Sarah reached intermediate, she was keen to shine at netball. In fact, it was her love of netball that initially sparked her passion for sport. “I really wanted to be a Silver Fern – Bernice Mene was a hero to me. Half Samoan, she played netball and did athletics at a young age, and that was it – I wanted to be her. When I was 12, I went on my first representative trip to Dunedin and sat next to her on the plane, which was amazing. Then she came and watched us compete; she’d been in the same competition when she was young. Seeing your heroes is powerful – and Sandra Edge and Chantal Brunner are others I really looked to as well.”

At high school, it was clear that rather than just excellent, Sarah was gifted. She began representing New Zealand at 16, and life became very busy with events and the overseas travel that came with it. That’s not to say her studies took a back seat, though. “I was never not expected to go to university,” says Sarah. “Sport is a vehicle. I got awarded the Prime Minister’s Scholarship, which funded two degrees, and I would’ve preferred to have been training. But I know the value of education, so I got a Bachelor of Health Sciences so I can work as a physiotherapist, and I’ve also got a BA in Communications.”

It’s hard not to be blown away by the sheer commitment that would have been involved in juggling study and part-time work with training and competing as a heptathlete, which is essentially a case of taking the top level of each code and multiplying the expectation by seven. The sheer physicality involved is mind-blowing, and alongside this the mental capacity required to keep up the momentum not just for a short burst, but for 48 hours. Adding into the mix the recovery time for each event and the fact that different sports are known to “peak” at different ages, how is it possible to excel?! I feel exhausted even contemplating it.

“It would’ve been a lot easier to pick one sport,” admits Sarah. “When I was eight, I watched the 1992 Olympics and I knew that’s what I wanted to do. My greatest potential in athletics was heptathlon as I was a natural jumper. I was resistant for a long time because I knew it would be hard and I’m not naturally a thrower, but in 2005 I roomed with a heptathlete and realised it was what I was most suited to. Five months later, I made the Commonwealth Games.”

Throughout this time, neither Sarah’s dedication nor her family’s support wavered, something that brought both amazing highs and undeniable lows. “Everything was focussed on the performance,” she says. “My friends were buying houses and I had a dollar in my bank account because I’d spent it all on supplements and massages. There were times when I was like, ‘I’m 28 and I haven’t done what I want in athletics yet, I’m single – what am I going to do with my life?’ You finish in your 30s with a lot of great skills but very little job experience.”

Still, Sarah says her ultimate high was when she qualified for the Olympics in Götzis, Austria. “I knew I was in good shape, but a really significant moment was in the high jump when I jumped 191; at the time my best had been 184. I was really free. For a long time, I’d put a handbrake on my life, and for the five years previous I hadn’t improved in the way I wanted to. For a long time, something had been holding me back. A year before, I probably wanted to quit, but I managed to turn it around, and in that high jump I finally unleashed what I was physically capable of. It was one of the purest moments of my life.”

The decision to step away from the world of international athletics in 2014 was similarly momentous, but at the same time natural. There was no big blow-out, no horrendous injury – the timing just seemed right. “I felt done,” says Sarah. “I was 30 and it seemed like a good time to retire. I got married the next year and in 2015 we had our first child, Max.” He was followed by daughter Poppy two years later. Nevertheless, going from training for five hours a day to a desk job was a huge shift, which Sarah says she struggled with.

“For so long in my life, I knew what I was aiming for, so to then have a blank canvas was hard. Immediately after retirement, I worked in marketing for one of my sponsors, Asics, and I loved the job, but I wasn’t expressing my physical gifts through a sport I love with people I love around me. And not being outside was a massive thing too.” Part of Sarah’s journey became identifying a new set of goals to satisfy her competitive nature. The excitement of becoming a mother was also part of the process, and the physical changes of pregnancy meant another mental shift. “It was a transition out of elite sport and out of a body I was used to being in, so I didn’t recognise myself,” says Sarah. “In some ways, it was a release for me to eat anything because I’d been on a performance diet.”

Fuelling her body differently was freeing, “but liberation created a disconnect about who I was and who I was becoming. I had no control – well, I had control over the chip packet! – but not over what was happening to my body.” Throughout this challenging period, Sarah was supported by her husband Angus Ross, a former Olympic sportsman who competed in bobsleigh events. Now a sports scientist, Angus was the perfect person to guide her on what she needed to do to stay well and nurture herself.

For the past few years, Sarah has been on a journey to redefine who she is. Her days are very different and elements of her psyche have undoubtedly changed, but acknowledging her core values has been central to her next chapter. “Self- acceptance became a really big part of who I wanted to be,” she says. “I ‘do’ athletics, but it’s not who I am. There’s a lot more to me than I realised, and sport is a mechanism for living my values, which are legacy, and love and courage.”

These days, Sarah says, her life is like a heptathlon. She’s equally passionate about all her projects, including Olympics- related governance positions, work as a marriage celebrant and as a columnist for online forum LockerRoom (at newsroom. co.nz), for which she exclusively covers women, advocating for them in sport. “I’m really grateful to shine a light on people and provide a platform for these stories to be heard,” Sarah says. As she well knows, it’s vital that young athletes coming through the ranks can find someone to identify with. “I know the power of seeing women in sport.” Sarah also acts as an Olympic ambassador in schools. Through talking about her own journey, she brings the Olympics to life for our youth and encourages kids to be active.

An exciting upcoming role is covering the Tokyo 2021 Olympic Games for TVNZ. Sarah’s thrilled to be a part of this; she’d watch the Olympics regardless, but in this capacity she gets to communicate what’s going on to our whole country. Plus, she says, she’s constantly looking for ways to stretch herself, and the buzz of live TV is similar to the rush of competing.

Despite moving out of the international arena, Sarah certainly hasn’t left sport, and still trains for and competes in triple jump events. “In 2017, I needed something to train for,” she says. “I always really wanted to do the triple jump, and I was highest ranked in Aotearoa. After I had Poppy, I thought I’d try it again, so last year I did and came second at the Nationals. This year, I had a back injury and got third.”

I marvel that she can switch back to the training and diet regime required. “It’s amazing that I still have that,” she concedes. “I can still turn it on. Saying no to things I know won’t help me is empowering.” That’s just another reason why Olympian Sarah Cowley Ross is a cut above the rest.

You can follow Sarah’s behind the scenes journey covering the Olympics on Instagram: @SARAHCOWLEYROSS

Tokyo 2020 TVNZ Presenter

“For the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, I’m excited to be presenting alongside Toni Street and Scotty Stevenson on TVNZ. We’ll bring all the top sporting moments to you every hour, as they happen. All the Kiwi news and more will be beamed straight back into our homes in Aotearoa. I’ll be cheering on my friends like Emma Twiggs in the sngle skulls. and all my sisters in the Black Ferms sevens team. And, of course, I can’t wait to see how the athletics events unfold.”

Governance roles

“A significant part of my work right now is as a board member of the New Zealand Olympic Committee and as chair of the NZOC Athletes’ Commission. The advocacy work in this role has created meaningful change for Team Aotearoa and the wider sports high-performance system. I enable athletes’ voices to come through the commission and into the boardroom. Athletes are very goal-oriented people, and want to see action come out of mahi. It’s vital they see their opinions being voiced.”

The Olympians of UNO: a look back at the stories from some of our local sporting heroes

We take a look back at some of our local sporting heroes that have graced UNO, and are currently involved in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games.

Sarah Hirini (neé Goss)

Sarah Hirini (Goss) carried the flag for New Zealand in the Tokyo 2020 Olympics opening ceremony and is playing in our women’s sevens rugby team but back in 2017 she was on the cover of UNO Magazine.

“It meant I was able to play whatever sport I wanted without my parents having to drive me around everywhere. It was all just there”. Gymnastics and netball transitioned into competitive hockey, and ultimately rugby in her final year at school. At the time, Sarah’s coach had recommended taking up rugby to help improve her fitness for hockey but she soon found the full contact and competitiveness of 15-aside rugby much more stimulating than hockey and as a result, traded her hockey stick for a pair of rugby boots. However, it was not a completely smooth transition into her newfound passion.

“I hid it from my parents for about three months, thinking they were going to tell me off for playing rugby. I felt like back then, there wasn’t much support for women’s rugby despite my family being massive rugby supporters.” But once Sarah decided to tell her parents of her new secret love, they were only disappointed they had missed watching her games and according to Sarah, “they’ve watched me ever since. I remember telling my parents back in the seventh form when they asked what I was going to do the following year and I remember saying I’m going to become a professional rugby player and back then they kind of laughed, but I am someone who will just go after it and I will do everything I can to prove people wrong. I’m stubborn, and it ended up happening.”

Read the full story on Sarah’s rise within rugby.

Peter Burling

Peter Burling has reached incredible heights since his cover story in UNO in spring 2017 and is currently sailing in Tokyo.

“At the Olympic level,” he says, “a lot of it is just a seat-of-your-pants kind of thing, because today you have a single platform that you can’t really change or improve.”

This is, after all, essentially a one-design race and everyone uses virtually identical equipment, so – as Burling says – “It’s a question of how you set it up and how well you can sail it!” But in something like the America’s Cup it’s different; the variables are almost infinite and change – literally – by the hour. And in that fast moving, high-tech environment, knowledge is power.

“I’ve always really liked the engineering side of sailing,” he says, “ever since I was a little kid and making things and trying things on the boats. I’ve always been quite pedantic on having a really clean and well-thought- out boat, not having anything on there that doesn’t need to be there, and having it all neat and tidy.”

Matt Scorringe

The New Zealand Olympic surfing team’s head coach graced the cover of UNO back in summer 2020.

One of the drivers of that change has been the acceptance of surfing as an Olympic sport. “Surfing,” says Matt, “particularly in New Zealand, is still seen differently to other major sports – and the Olympics will change that. It will mean we start to take things seriously and start working towards finding the best path for our athletes at Olympic level. I’ve talked with friends in snowboarding and other sports that have recently been made Olympic sports and they all say it takes time. It’s like the chicken and the egg – you need funding to get results, you need results to get funding – but it’s great to see that we’re off to a really good start with two athletes going to Tokyo.”

Matt’s role in preparing those Olympic contenders has been as head coach of the development pathways programme he helped put together to get our surfers up to Olympic qualifying level, and he’s more than happy with the results. “We’ve now got two athletes qualified for the 2020 Olympics – Billy Simon from Raglan and Ella Williams from Whangamata – who both came through that programme. Now we just need to get some more structures and mechanisms in place to support them and the sport. At that level, you don’t spend a lot of time at home; you’re travelling all the time, so you need coaches, nutritionists and all the support required on different continents. Part of what I’m doing is not just bringing my knowledge but the connections and contacts to make it easier.”

Sarah Cowley Ross

Our most recent cover star, Olympic and Commonwealth Games heptathlete Sarah Cowley Ross is currently a huge presence in media coverage of the Games.

Sarah says her ultimate high was when she qualified for the Olympics in Götzis, Austria. “I knew I was in good shape, but a really significant moment was in the high jump when I jumped 191; at the time my best had been 184. I was really free. For a long time, I’d put a handbrake on my life, and for the five years previous I hadn’t improved in the way I wanted to.

A year before, I probably wanted to quit, but I managed to turn it around, and in that high jump I finally unleashed what I was physically capable of. It was one of the purest moments of my life.”

Turning accomplished surfers into frothing groms

“After being an accomplished surfer, going back to being a total learner can be quite a humbling experience, but it’s also an opportunity to get that buzz of your first successful ride, which a lot of us who’ve been surfing for a lifetime have forgotten.”

Catch the wave with a Mount man who’s thrilled to have found his passion and to be helping others find it too.

WORDS + PHOTOS Katie Cox

In July 2016, Mt Maunganui’s Geoff Cox had been working as a videographer in the film and television industry for nearly two decades when he disappeared into his shed. Three days and much tinkering later, he emerged with a prototype of a foilboard he’d shaped. Cut to today and he’s working with Signature Performance Gear to help surfers all over the world take wave-riding to a new dimension.

Getting with it

Not even sure what a foilboard is? It’s sort of like a surfboard but with a hydrofoil that extends down into the water. “To put it simply, it’s a glider flying underwater,” says Geoff. “Just like an aeroplane wing, there’s a foil section that generates lift when you’re moving forward. The unique element of surf foiling is that all of the energy comes from the wave – no kite, no sail, no motor. One of the most rewarding things about surf foiling is learning to feel that energy and get better at finding and using it.”

Geoff was inspired to become a shaper by watching Hawaiian surfer Kai Lenny paddle in on a foil. “It was the first time I’d seen surf foiling not involving jet skis and tow ropes and all of those layers of complexity that make it less accessible. To me, it looked like the ultimate evolution of wave riding.”

The first few foils he shaped were totally experimental; there were very few surf foils on the market and he hadn’t seen any in person. “There were foils that were made for kite foiling, but they weren't fit for the purpose of foil surfing,” he recalls.

Refining the process

In the beginning, Geoff’s process was labour- and time-intensive, much like hand-shaping a surfboard. “I started with a hand-cut foam core that was then hand-laminated in carbon and epoxy,” he says. “It involved lots of sanding and there was a lot of inaccuracy in the design.”

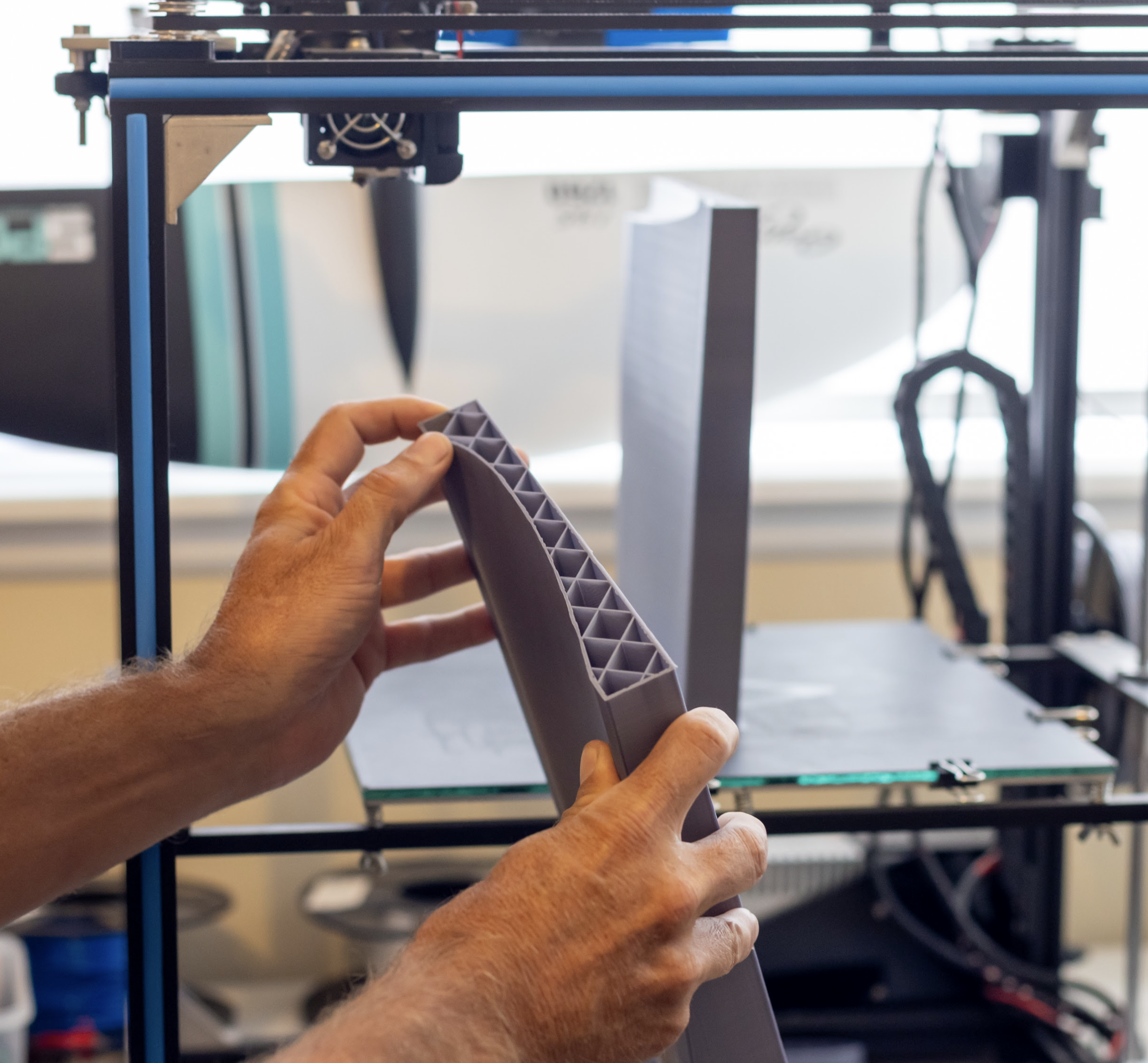

But things got better. As part of his design background, Geoff had always been conversant in computer-animated design (CAD), so he started designing his foils that way. “I built a 3D printer that allowed me to very accurately create my CAD designs as 3D-printed molds, which I’d then use to lay up the foils in,” he says. “This accuracy allowed me to repeat designs while changing and refining features to get the performance I was after.”

Three years on from his first foray, in late 2019, Geoff was entertaining the idea of producing a small run of his foils and testing the market to see if it was worth pursuing further. While communicating with a composite factory about manufacturing them, his contact at the factory mentioned that he knew of a global surf brand that was looking for foil designers to help them develop their existing offerings. That company was Signature Performance Gear.

“He connected us and it went from there,” says Geoff. “The SPG family are an amazing group of people and I’m so stoked to be part of the team. I could not have found a better brand to get involved with.”

Moving on up

The wing Geoff designed for Signature Performance Gear has been met with rave reviews worldwide by some of the major influencers in the sport. “Part of what I did for Signature was update the existing range into a modular system, which involved redesigning every component – the mast, fuselage, tails and existing wings,” says Geoff. “The second part was adding my model, called the GameChanger, to the range.”

Building moulds for commercial production is an expensive process, but Signature invested in Geoff’s model fully trusting it was a good design. “I’d just returned from Tahiti, where I’d surfed my latest design in a wide range of conditions and it was just so good!” says Geoff. “I had a lot of confidence in it, but it’d only been ridden by me and my friends. When the first production models started getting shipped out to the world's top riders and influencers, I was quietly shitting myself, hoping it’d be well received. I had a lot of sleepless nights! And then the first reviews started hitting Instagram wiith 100% positive feedback.”

So how does it feel to know that a design that came out of your head is now under the feet of some of the world's best riders? “I’m just buzzing when I see what guys are doing on my foil,” says Geoff. “I guess it's the same feeling a surfboard shaper gets seeing a surfer improve on their shapes. Locally, Alex Dive is one of the best around and his foiling took a huge leap forward when he got on my foil – he’s pushing his performance to the next level. Internationally, the response is amazing. Seeing videos of the best guys going off on my design is hugely rewarding.”

Sharing the love

A lot of the world's top surfers are now into foiling too, and Geoff thinks they’re drawn by the excitement of a new challenge. “It's a very difficult thing to do, so it’s very rewarding when you start to get it,” says Geoff. “It really is just an amazing feeling – it feels like flying. That’s very different to being confined to the water surface and the bumps and chop that go with it.”

Foiling has changed the types of waves Geoff and others ride, and the way they ride them too. “So many waves that aren’t great for surfing are perfect for the foil, and we’ll often have eight or 10 of us all sharing waves and connecting up multiple rides and pumping back out to share more,” he says. “Living at the Mount, the good surfable days have gone from 50 a year to 200.”

Keen to join the party? Geoff says the learning process is probably harder on the ego than anything else. “After being an accomplished surfer, going back to being a total learner can be quite a humbling experience, but it’s also an opportunity to get that buzz of your first successful ride, which a lot of us who’ve been surfing for a lifetime have forgotten. I love how all my ‘older’ friends have become frothing grommets who just can't get enough!”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Giving back to the community beyond crisis: Todd Hilleard of Noxen

“I ran at her and tackled her onto the bed. She still had the gun in her hand but now it was pointed at me. I kept thinking, ‘Is this real?’”

“I ran at her and tackled her onto the bed. She still had the gun in her hand but now it was pointed at me. I kept thinking, ‘Is this real?’”

WORDS Ellen Brook

Todd Hilleard was passionate about being a police officer, but a routine callout turned armed confrontation was the first in a series of events that changed his state of mind. Todd had been talking to a woman who had allegedly assaulted her husband when suddenly she pulled out a pistol, held it to her head, and threatened to shoot herself.

“It was a horrible situation,” recalls Todd. “Everything was happening in slow motion and I felt awful to be pinning this woman down, trying to force the gun from her hands.It was my first time in a situation which came from nowhere and involved a firearm. I was completely unprepared for it.”

Later, Todd was rattled when a driver he’d stopped unexpectedly reached under the seat of his car. “I was worried he might be reaching for a gun, and it put me on edge,” says Todd.

After another event where a shotgun was thought to be in the vehicle of a father who had abducted his children, Todd realised he wasn’t coping. The Police transferred him from Tauranga to Christchurch, his hometown, hoping the fresh start would improve his mental health.

But the September 2010 earthquake made Todd even more anxious. “Afterwards, I was on edge.I didn’t feel comfortable in my own skin, especially going out on jobs in the middle of the night.”

During the second earthquake in February 2011, Todd was at work on the third floor of the Christchurch Central Police Station. “The alarms went on and on, and I expected the building to come down,” says Todd. “I was terrified.”

Todd didn’t have time to dwell on his fear; he was immediately sent to the CTV building which had collapsed like a concertina, killing 115 people and trapping many more. “Other cops were on top of the rubble, but I thought, ‘I can’t be here, I’m scared’," says Todd. He stayed at the scene for 12 hours. “It was chaos. I saw terrible things you hope to never see.”

There were also bright spots. Todd and his fiancée Tash were planning their wedding, and he was working on a rewarding project organising the recovery of vehicles trapped in Christchurch’s Red Zone. But the day after his stag party, Todd went to hospital with heart palpitations. He then had an allergic reaction to the drug he was given and went into anaphylactic shock. His heart needed electrical cardioversion to restart its normal rhythm.electrical cardioversion, a high-energy shock sent to the heart to restart its normal rhythm. Todd was devastated.

“I couldn’t believe this was happening to me at 30 years old,” says Todd. “I was beside myself at the thought of my heart stopping.”

Todd married Tash in April 2011. Although the wedding was a happy occasion, Todd hit rock bottom soon afterward. “I was driving to the movies when I started to have chest pains,” says Todd. “I went to the hospital, but my heart wasn’t the problem. I was having a panic attack.”

After the birth of their baby boy, Tate, Todd woke up one morning in 2011 and knew he couldn’t go back to work. “It was time for me to stop fighting.I felt quite euphoric about that.”

He went on sick leave from the Police, and then leave without pay. Soon after, Tash, then 24 weeks pregnant with their daughter Lexi was made redundant and the young family moved back to Tauranga. Todd found solace in the local surfing scene, but he’d lost his identity as a police officer. “I’d be out and see police cars with my old mates in them. It took a long time to accept what had happened,” says Todd. He finally resigned from his job in 2013.

Although he’d left the Police, Todd’s mental health was still poor. At his lowest point, he even considered suicide. “My twisted thoughts were my biggest battle. They put me in a very dark place and I worried I was going crazy,” says Todd. “I finally got help through my doctor, went to therapy and realised that talking openly and rawly and letting myself be vulnerable really helped.”

Todd returned to the workforce in sales at Coca-Cola and then Goodman Fielder, and stayed involved in the surfing scene. His love of the sport led him to the next chapter of his career. Taking part in the 2018 Police Association Surfing Champs in Raglan, Todd noticed that at 1.8 metres and 90kg, the XL-sized hooded towelling poncho Todd received as a souvenir of the event was too small for him. He began researching similar products and looking at samples. When he found what he wanted, he set up Noxen (noxen.co.nz), an online surf and lifestyle clothing business.

For Todd, what started as a solution to one problem has become a way for him to give back to the community. The brand’s tagline “Ride Every Wave” reminds Todd to ride out life’s ups and downs. A percentage of each sale goes to Lifeline, the mental health and suicide prevention hotline, and a further percentage of sales revenue is donated to other charitable causes.

Todd continues to be open about his mental health, both on the Noxen website and at speaking engagements. He acknowledges that his experiences changed his ability to manage things the way he used to. “I’ll never be fully back,” says Todd. “I’ll always have anxiety and depression, but I can manage it, and now I have an opportunity to pay it forward.”

WHERE TO GET HELP

Sometimes it helps to know someone is listening and that you don’t have to face your problems alone.

0800 LIFELINE

Youthline 0800376633

Free text 234, email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat.

Path of progress: Motu Trails, Opotiki

How a decade-old cycle trail is delighting both tourists and the local community contributing to its success.

How a decade-old cycle trail is delighting both tourists and the local community contributing to its success.

WORDS Sue Hoffart PHOTOS Jim Robinson, Neil Robert Hutton + Cam Mackenzie

A scenic dunes trail that has resolved a watery paradox for the coastal town of Opōtiki is proving a massive drawcard for both locals and tourists.

Ancient waka travellers and modern-day boat owners have always been able to access the ocean by way of twin rivers that wrap around the Eastern Bay of Plenty township. But it took a cycle trail and handsome suspension bridge spanning Otara River to connect walkers, joggers and bikers with the gloriously long stretch of coastline on their doorstep.

Most of the spectacular Motu Trails cycleway network lies inland, where rugged grade three and four tracks attract hardy mountain bikers keen to test themselves on backcountry roads and steep forest trails. Collectively, they range over 30km of track and more than 150km of gravel and backcountry roads. The most mellow section, though, begins with a pedestrian bridge on the northern edge of town and a delightfully scenic, undulating gravel track running parallel to the shoreline.

Increasing popularity

It is this 9km grade two “dunes trail” that has given the town its beach, according to tourism operator and local resident Volker Grindel. The decade-old trail has become increasingly popular with Opotiki people and visitors.

“Before, everyone needed a car to get to the beach,” Volker says.

These days local children and carless residents can reach the coast safely on foot, by crossing the Pakowhai ki Otutaopuku bridge, rather than having to walk more than 3km along the highway and side road. So too can tourists who arrive by bus or bike. After crossing the river, the trail meanders past grazing Friesian cows and opens onto views of the East Cape and nearby Moutohorā (Whale Island).

“The dunes section is the most used part of the Motu Trails,” Volker says.

“The town kids and people who live here use it a lot for fitness; running, jogging. And the kids who live out of town use it to come to school on their bikes because it’s safer than the highway. I’ve even seen a little fella with training wheels.”

Happy accident

Volker and his wife Andrea operate a small backpackers’ hostel and Andrea runs their busy Kafe Friends coffee cart just off the main street. The German-born couple, who met in Opotiki after her car broke down there, are seeing increasing numbers of day trippers in bike gear from nearby Rotorua, Whakatane and Tauranga.

He says Tirohanga Beach Motor Camp, part way along the dunes, is packed with people using bikes during summer holidays and weekends. Plenty of those campers and cycle tourists make their way along the trail to the town centre.

“Before, they were not taking their kids on that busy road. Now, they come here to town do some shopping, drop in for coffee here or somewhere else. So the Four Square, the New World, the gas stations all get something out of this trail, too.”

Andrea runs along the dunes when she is training for half-marathons, and it is used by dog walkers and local schools that have been inspired to run duathlons and small cycle events for students.

Long-time volunteer trail builder, keen biker and Motu Trails executive officer Jim Robinson does track assessments, as well as overseeing signage, the trails website and Facebook page and multiple other roles. He laughs at his fancy title and stresses the trust-run operation is small and heavily reliant on unpaid community involvement, as well as council and conservation department input. But he says there is no doubting the Motu social and economic benefits, or its standing as a ‘great ride’ of Ngā Haerenga, the New Zealand Cycle Trail.

He is especially enthused by the ongoing planting and beautification programme that has transformed the “really important but environmentally degraded” sand dunes area with the help of about 20,000 flax bushes, cabbage trees, pōhutukawa and other native plants. All have been poked into the ground by volunteers, with another three planting days planned this winter.

Jim says one section of coastline now occupied by the dunes trail had been used for dumping rubbish, other parts had been grazed by stock, or were covered in gorse, kikuyu, boxthorn, pampas and other undesirable invaders.

Points of interest

Interpretive signs denote culturally significant areas, including historic landing sites and burial grounds, and the track route was chosen to avoid especially sacred or sensitive sites.

Local potters and environmentalists Margaret and Stuart Slade provided handmade ceramic tiles depicting birds, mounted on concrete culverts to create sturdy sculpture. Earlier artworks were provided by schoolchildren who painted wooden cut-outs of birds and animals as a conservation week project.

Small tourism operators have sprung up to offer farmstay accommodation, food or shuttle transport to mountain bikers using the trails that connect Opotiki to Gisborne.

Late last year, long-time kayak tour operator Kenny McCracken began offering guided bike tours along the dunes, incorporating local history and food, with an optional swim along the way.

“There’s a massive amount of community ownership of the trail,” Jim says.

Throwback: Liam Messam looks back at his 2006 UNO cover

Liam Messam went straight from Rotorua Boys' High School into the New Zealand Sevens Squad and began his full time rugby professional career. He was just 21 years old when he starred on the cover of UNO.

THEN

Liam Messam went straight from Rotorua Boys' High School into the New Zealand Sevens Squad and began his full time rugby professional career. He was just 21 years old when he starred on the cover.

NOW

I must have had a full tub of Dax Wax in my hair. I laugh now when I see the cover, all styled up with the clothes and 'do.

Back then I was totally immersed, committed and focused. It was almost an obsession to be the best player I could be.

The highlight of my career? The friends I've made. Although, winning the Rugby World Cup in 2015 was up there, too! We had such an awesome culture within the team.

In August, I'm off to Toulon in France. The rugby will be fantastic. I've been to Paris and Marseille a couple of times, but this will be a completely different experience.

My two boys, Jai and Bodie, they are learning a few words in French to set them up for a new life in France.

I have such passion and love for the game, I'll keep playing until my body can't take it anymore. As for a career afterwards, I'd like to work in youth leadership, and of course, health and fitness.

Drifting through life

Jodie Verhulst is the number one female drift car driver in the country, and watching her drive is phenomenal. Her arms and legs move at highspeed, as if she is performing a type of dance, but her demeanour is cool, calm and collected.

“There’s a lot to think about at such high speed. It’s a guessing game as to where the other car is because you often can’t see anything through plumes of smoke.”

WORDS TALIA WALDEGRAVE / PHOTOS JAHL MARSHALL

Jodie Verhulst is the number one female drift car driver in the country and watching her drive is phenomenal. Her arms and legs move at rapid speed, as if she is performing a type of dance, but her demeanor is cool, calm and collected.

“It’s really just muscle memory and I don’t even know what I’m doing half the time.”

Jodie is one of the nicest people I think I’ve ever met. My editor, introduced us with the words, “Goodness, don’t you two look alike?” Jodie nods, smiling politely, but all I can do is blush. I certainly don’t see a similarity but am humbled in any way to be likened to this beauty.

It is the hottest day of summer and we are at the D1NZ Drifting Championship, at ASB Baypark Arena. It is an assault on the senses. Stifling heat is intensified by the compulsory wearing of closed-toed shoes and the noise is like nothing I’ve ever heard; piercing and shocking, it sends vibrations rattling through my entire body. The smell is an overwhelming combination of petrol, dust and burning rubber. Cars come at me from every direction and it pays to be on high alert. It’s ridiculously exciting.

You'd be forgiven if like me, you were not entirely sure what drifting is. Don't tell any of the lads in my life because along with the photographer from this shoot, they'll either scoff at, or disown me for admitting my ignorance. I had to google drifting and back it up with YouTube to work it out. Drifting is a technique in which a driver deliberately over-steers, losing traction while maintaining control. It’s all about showmanship, angle, speed and line.

I meet with Jodie a few days later and her explanation is far more relatable.

“Drifting is like ballet but with two cars. You mimic the car in front and getting as close as you can without touching. There are two laps, one when you’re the leader, one when you’re the chaser. It’s a different sport to get your ahead around in the beginning, because instead of breaking into the corner, you actually accelerate.”

I’m in awe of this impressive woman who is killing it, in what is seemingly a man’s world.

“Although we live in a time where there’s a balance between the sexes, you definitely feel a bit of pressure being one of the only females.”

“My brother introduced me to cars and my partner Drew introduced me to drifting, and it was all downhill from there.”

“The response this weekend at the Championships has blown me away. I’ve had women coming up to me saying how much they love my driving, even the older ones. I’ll often catch some of the shyer, young girls out of the corner of my eye and I love to be able to give them something real to look up to other than pop stars or film stars. That especially, is a highlight with what I do. Although it’s just a bi-product of my driving, it makes me really happy, it’s really cool.”

Jodie’s partner Drew is the other half of her team and together they live and breathe all things drifting. I comment that she is very brave working so closely with her partner in such an intense environment, many relationships wouldn’t be able to weather it.

“Drew has been an incredible mentor. He’s been one step ahead of me the whole time. I’m very lucky because it doesn’t matter to him that his partner is out there battling and might do better than him. I’d love to go head-to-head with him in a battle, there’d be no holds barred and I think there’d be a lot of damage to the cars!”

This leads me to question the safety in drifting. I found myself on edge of my seat for the duration of each race - it’s hair-raisingly scary.

“We’re increasing speeds and making the cars lighter, so it’s risky, but safety always comes first. We have a cage, harnesses and helmets, so compared to other sports, it’s quite safe.”

“If you’re not getting that feeling of nerves and adrenaline, and if you’re not scaring yourself, then you’re not pushing hard enough. It’s very powerful and you definitely work up a good sweat. I’ll be drenched by the end of today. Getting into the car is like stepping into a sauna.”

Jodie’s sweet nature seems contradictory to someone who would head into battle, deliberately aiming to knock out her opponent. It’s clear that drifting, like all sport, is incredibly competitive.

“It’s a tough sport, and in the last two years, the gap has closed so much between competitive drivers. You have to do something special and really push the boundaries to stand out. I’m competing against people who have been in the sport five or six years longer than me, so I really have to go as hard as I can. It’s about more speed, sharper angles.”

Heightening this adrenalin-fuelled atmosphere are the fans. “The atmosphere at Baypark is insane, particularly as this is our home track. We’ve had people yelling in our ears and getting right in our faces, but that’s all part of the build up and adds to the excitement. When the drivers were introduced last night in the preliminary round and my name was called, I couldn’t believe it. The audience just went nuts. There’s just nothing like that and I’ll never forget it, not for my entire life. I was actually choking up a little bit.”

I mention that a lot of my friends have been talking about her, without knowing about our interview. “There are a lot of closet drifters out there I think!”

Jodie tries to get me into the car so she can give me a ‘hot lap.’ I have absolutely no qualms in telling you all, I firmly declined. Save your tyres, save your petrol and use it far more wisely on someone else. I’ll be sitting firmly on the edge of my seat.

Something in the water

His face is already pretty much etched into the national psyche, and that easy smile and cool, calm demeanor have become known around the world, but in person, Peter Burling could not be more humble, more unassuming, or any more relaxed.

His face is already pretty much etched into the national psyche, and that easy smile and cool, calm demeanor have become known around the world, but in person, Peter Burling could not be more humble, more unassuming, or any more relaxed.

He may be an Olympic gold medal winner with a string of international titles to boot, and of course there is that not insignificant matter of bringing the America’s Cup back to its rightful home here in New Zealand, but in the flesh the man responsible for whipping a multi-million dollar boat through water at speeds approaching 100 km per hour is just a sweet-natured, very casual, amiable twenty-something. He’s arguably the world’s best sailor, but at heart he is still just a boy from the Bay, unfazed and unchanged by fame and more than willing to spend some time in front of the camera and talk to UNO about the journey so far.

It is a journey that began around 20 years ago in the Welcome Bay estuary, where an eight-year-old Burling and his brother first set sail in Jelly Tip, a wooden Optimist-class yacht that had definitely seen better days. “My brother got into it first and I just kinda got dragged along,” Burling says of his earliest foray into sailing, with that trademark understatement. “My Dad had been into sailing and thought it was a good skill to have. And it kind of spiralled from there.”

And when he says spiralled, he means it whirled wildly and unstoppably onto national then international stages: he won his first Optimist nationals at nine years of age, competed in the World Champs in Texas aged 12, and scooped the 2006 420 Class Worlds title in the Canary Islands at the tender age of just 15; a year later he won the Under-18 World Championship, took the 49er World Champs with Blair Tuke in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, and – again with Tuke – took home silver in the 2012 Olympics and gold in the 2016 event. Then came the America’s Cup and the New Zealand Order of Merit for Services to Sailing, but before we go there, lets just back up the bus and get back to Welcome Bay in the early noughties.

“I have a lot of fond memories of that time,” Burling says. “Around here can be a pretty tricky place to sail, but one of the cool things about it is that you can sail in any conditions. In a lot of places you end up sailing in only one type of weather, but here, because you can get out in all kinds, it means you are quite well- rounded as you’ve had to deal with a lot of different things and looked at different ways of wining races - if you want to, you can sail in some pretty big swells at times here! The other cool thing about Tauranga is you have the keel boat club and the dinghies kind of just in one group, with adults and younger ones competing. It’s unique in that there is everything from the Learn to Sail level right on up to the keel boat club, and there’s not many around the country that have that.”

The sailing environment he encountered in Bermuda with the America’s Cup Challenge also had similarities to his early escapades on the sea around Tauranga, with a relatively limited area of open water and changeable conditions; but perhaps the main thing his formative years taught him was adaptability, a decidedly Kiwi trait if ever there was one. “One of the skills I did learn here at a young age was to be able to watch other people do a sport and to learn off them, to notice different things about how they’re sailing and have things set up, and to be able to adapt things really quickly and see whether you are sailing well or not. A large percentage of our sport is how quickly you can get the boat to go, and when people say someone is a natural sailor, they mean that person has an instinctive way of getting a boat to go faster than it should. And that is something learnt from hours of getting things balanced and learning about what is fast and what isn’t.”

And whatever happened to Jelly Tip? “I honestly don’t know,” Burling shrugs. “I’m not even sure if it was even my boat. Jelly Tip was bought for my brother and I ended up with it. . . Who knows where it is now.” Somewhere in Tauranga, someone may just have a piece of sailing history sitting in the backyard.

As Burling’s skills grew and the awards piled up – repeated questions about when the silverware outgrew the mantle piece and where they live now are all answered with a sheepish shrug and deflective smile – he also had to learn how to juggle his competitive life and the more mundane aspects of youth. Like getting an education.

Having attended Tauranga Boys College (at the same time coincidentally as cricketer Kane Williamson), he embarked on a mechanical engineering degree at Auckland University, but half way through, in his words, he decided to “major in sailing” instead. Competing in European sailing at pretty high levels and then coming back to try and focus on exams was probably never going to work, but while he may not have come out with a degree, he is the first to admit that two years of engineering studies eventually paid off on the water.

“At the Olympic level,” he says, “a lot of it is just a seat-of- your-pants kind of thing, because today you have a single platform that you can’t really change or improve.”

This is, after all, essentially a one-design race and everyone uses virtually identical equipment, so – as Burling says – “It’s a question of how you set it up and how well you can sail it!” But in something like the Americas Cup it’s different; the variables are almost infinite and change – literally – by the hour. And in that fast moving, high-tech environment, knowledge is power.

“I’ve always really liked the engineering side of sailing,” he says, “ever since I was a little kid and making things and trying things on the boats. I’ve always been quite pedantic on having a really clean and well-thought- out boat, not having anything on there that doesn’t need to be there, and having it all neat and tidy.”

And he would be the first to admit that this has translated from the waters of Welcome Bay to Bermuda. “I do feel like I had a good understanding of the systems on board and our team had a strength in the link between the sailing team and the designers, so that we knew how hard we could push it,” he says, again with an achingly acute sense of understatement. “At the end of the day, we are the ones who have to decide whether to back off or take the risk and play the game. But that is always something that I really loved, that whole side of it.”

If it sounds like a calculated risk, it is. Burling has described international level competitive sailing as being a massive game of chess, and though he finesses that description a little, it is clear he still sees it that way in his mind. “It’s a little different,” he says, “in that you can slightly change your pieces from time to time. But yeah, the better you are the less mistakes you make. And while you have to have an underlying plan, you also have to wing it sometimes.

And just as on the board, so too on the water, it is often he who dares – wings it but errs on the right side of the parameters – that wins. As we all saw played out on our

TV screens, in this level of competition things can go spectacularly wrong, and when they do, they do so at speed. Who can forget the heart stopping minutes that stretched in to hours when it seemed New Zealand’s America’s Cup challenge had nose-dived figuratively and literally. But pushing things to the limits, and recovering from the results of dancing too close to those limits, is what marks the difference between winning and losing.

“They’re incredibly cool boats that we sailed in Bermuda,” Burling says. “We were really pushing the technology side in regard to what you could and couldn’t do, particularly in regard to the structural side of things, and there are so many decisions to be made in regard to how many risks to take in regard to that structure. On the windy days during the Cup, you were really looking at the loads on everything! And whether it was luck or good management we seemed to have got it pretty right.”

‘We’ is a very common word in the vocabulary of Peter Burling. It is not the royal

‘We’, it’s just ‘we’ as in ‘us’, in lower case, and it is striking how even in his own mind he edits out Peter Burling and defaults to the team persona. Striking, and also remarkably endearing in someone who is clearly such a very competitive person; you don’t take home the huge string of awards Burling has amassed without wanting to win, though he confesses – a little apologetically – that he’s forgotten just how many World Champs or 49ers wins he has: “You’d have to look it up,” he says.

“I’ve always been fairly competitive,” he admits, and that really is an understatement, “but I think we have gone through a period in New Zealand when we had heaps of people who were really competitive and who were pushing each other forward. And that has left us in pretty good stead for what we are doing today.

You learn that you have to keep improving and be your own critic and not really rely on too many people to help you out. We had quite minimal coaching when we were young, so that tends to make you more self reliant, and in this sport that is pretty important.”

Burling had barely been back on dry land – and yes he is aware that a huge chunk of his life is spent on the water – when he entered the international Moth class World

Champs at Lake Garda in Italy, and with almost no prep time he placed a very creditable second. Then it was back to New Zealand to continue touring the Cup, but along the way he announced that he would be joining Team Brunel in the Volvo Ocean Race, a decision that will put him up against his long time sailing partner Blair Tuke, who will be part of a different team in the race. The Volvo, formerly known as the Whitbread Round the World Race, demands a whole new skill set, with the crews being expected to much more than just sailors – medical response, sail making, engine and hydraulics repairs are all par for the course, and some legs of the race can last for up to 20 days. It ain’t for the faint hearted.

But having mastered everything from the one-man Moth class to the finely choreographed racing of the America’s Cup, it seems only fitting that he turns his talents to a new challenge. “Its something I’ve always seen as the other side of our sport,” Burling says, “and it has been a great opportunity to jump in with a team that is going to be on the pace. But we’ll have to wait and see how competitive we are, though it will be really good fun and a great chance to develop some skills. I enjoy change and variation and that is why I like doing other events and finding other ways to improve yourself. Everyday is different.”

In addition to being a remarkable success story, perhaps what we like about Peter

Burling is not just the dedication, the classic Kiwi can-do attitude and the team spirit, but the ability to do it all with a composure that borders on, well, almost disinterest.

The perfect antidote to the white-knuckle rides of the America’s Cup Challenge races were Burling’s pitch perfect performances in the post-race press conferences. He was famously accused of being asleep at the wheel, but his opposition and TV viewers alike soon found that to underestimate Peter Burling was to make a grave mistake. By the final races, more than one commentator was calling Burling’s deadpan delivery on and off the water his secret weapon, a star-turn that both baffled - and incrementally and incredibly infuriated - his opposing skipper.

“Yeah,” he says, slipping into trademark laconic post-race monotone, “it’s always been something that, from a young age, there has been pressure in competing and

I’ve always enjoyed that. I generally bring the best out of myself when I have a bit of pressure on, when you are racing for something rather than just going out for a sail.

But during the Cup, you always look quite relaxed because you know what is going on in the background and you know there are so many bits and pieces in place and obviously you have to perform really well and there is a lot of pressure, but you try to get a nice easy message out and keep everyone nice and relaxed. The main part of my job is to sail the boat fast, and we definitely did a good job of that as a team. We had some pretty tough situations to overcome at times, but we pulled through those pretty well. Having to pull through some bit and pieces – some are public knowledge and some aren’t – pulls you closer together and once we got past that first weekend, when we knew we were in with a chance, I don’t think we were ever going to let it go.”

Bits and pieces. Those would be the near total disaster of a wrecked boat, quite possibly injury or death, and the dashed hopes of a nation who were waiting and watching eagerly at home. But as we know they overcame the bits and pieces – the public and not so public – and took home the sailing world’s greatest trophy.

“The awards are not really why we do it,’ Burling says, “but it is cool to be recognized for what we’ve managed to achieve.” There’s that we again, but then – lo and behold – there is also a brief flash of just Peter Burling. “For me, a lot of it’s about having fun along the way. Win or lose, at the end of it you want to have had fun doing it,” he says.

And behind the cool, calm exterior and the laid back public persona, behind the calculated risk taker and the perennial team player, that is all you probably need to know about Peter Burling. It’s about having fun.

Siblings surfing: Jonas and Elin Tawharu

Jenny Rudd meets two of the world’s top junior surfers, brother and sister, Elin (15) and Jonas (17) Tawharu. They have grown up surfing on their doorstep, here in The Mount.

Jenny Rudd meets two of the world’s top junior surfers, brother and sister, Elin (15) and Jonas (17) Tawharu. They have grown up surfing on their doorstep, here in The Mount.

WORDS JENNY RUDD PHOTOS JEREME AUBERTIN, SALINA GALVAN + CAM NEATE

“Representing New Zealand in any sport gives you the grit and resilience needed to get through difficult times in life.” John Tawharu is the father of Elin and Jonas, two of New Zealand’s brightest surfing stars.

The siblings have just returned from the Azores in Portugal, where they competed in the 2016 VISSLA ISA World Junior Surfing Championship. Elin came 3rd in the U16 girls’ division (the first Kiwi podium finish in nine years), and Jonas was the top Kiwi competitor in the U18 boys’ division. This year was the biggest in the competition’s history, with 370 competitors from five continents, and the first in the era of surfing as an Olympic sport.

We meet Elin and Jonas at the UNO office. In their Mount College uniforms, they look like any other teens, but they are world-class athletes competing at the highest possible level.

IN THE BLOOD

There’s a fair bit of sporty blood flowing through the family; John, a teacher at Omanu Primary School, has represented New Zealand in softball and rugby. Step-mum Jo teaches at Tauranga Intermediate. They both coach the surfing teams at their respective schools. Jo has toured with the New Zealand women’s team as a qualified judge.

“My children have grown up surfing at every opportunity,” says John. “Living by Moa Park in The Mount, they have always been able to skip across the road in their wetsuits. Every weekend for years has been taken up with surfing, either here at home, or out on one of our infamous weekend surf missions. We study the weather reports, checking swell and wind conditions, work out where the best surf will be, and leap into action. It’s such an exciting way to live. Jo makes a stack of homemade pizzas the night before, and we start getting chilly bins, portable chairs, and all our kit out of the basement; everyone’s hunting around for wetsuits, fins, boards and sun-block.”

“Jonas decides exactly what time we need to leave to get the tide at its best, and I always say that Jo is our lucky charm: she almost always calls the surf conditions bang on. The adrenaline’s pumping as we round the last few corners, desperate to get a glimpse of the waves after a few hours on the road. I’ve lost count of the number of times we have zoomed down that hill at Manu Bay, Raglan! I feel very lucky to do these adventures with my partner and children.”

WAVE AFTER WAVE

The ocean has been the backdrop to Elin’s and Jonas’s lives. As toddlers, John would kick a ball into the waves. They would dive in and scoop it up, so the water splashed on their faces, giving them confidence in the water. As small children, John took them out boogie boarding in the rougher white water, to teach them about the power of the ocean. “Ever since she was little, I have always called Elin my Storm Girl. I’d take her out in cyclones, when the white water was smashing around all over the place. She just loved getting rumbled over and over in the waves, and even now she doesn’t ever care about being smashed by huge, dumping waves. That’s her thing – gnarly waves. Jo calls her the Queen of Gnarly.

“As a youngster, Jonas would surf all day with no rest, wearing himself out completely. Then he’d be wrecked for a few days. He’s had to learn to come in and get food and drink every few hours. He has an analytical mind, and has always been particular about his technique, practising over and over again to get it right. Jonas’s love of physics and interest in how things work is ingrained in him; as a nine-year-old, he gave me a lesson on weight transference on his skateboard!“

“The surf season is long and hectic, running from January through to November. And expensive. All us parents worry about how we are going to find the thousands of dollars needed for travel and accommodation as we take our children on the national tour. If they make the national team and go to the World Championships, it’s even more expensive. It always comes together, though. We fundraise hard, doing movie nights, garage sales, and car washing. And the community really gets behind us, which is fantastic. Jo is our master-organiser in the family, making sure everything stays on track. Everything clicks when she’s on board; her brain is amazing.”

ELIN

“Dad used to push me into two-foot, glassy waves on his fat fish board when I was little, and I would try and stand up. It was exhilarating, and I was hooked. Those are my earliest memories of surfing at my local break, Crossroads. Learning to surf at The Mount has given us such a great advantage. There’s so much coastline here, and the curves, peninsulas and islands create lots of different waves. The Mount has produced a lot of good competition surfers, as it’s a beach break, which is changeable. You have to be flexible to adapt. If you always surf a point break or river mouth, you don’t get enough practice with the smaller, slushy waves.

EARLY ADOPTER

I picked up surfing properly when I was nine. I’ve always been competitive by nature, and won my first national competition when I was eleven, in Taranaki. I was given a greenstone surfboard trophy. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that feeling. And being round the professional surfers was the most exciting thing I’d ever experienced: watching them sign autographs, have their photos taken, and engage in awkward chatter with fans (like me!). Just to be near them, I was frothing as a grom. I wanted to dress like them, look like them and, one day, surf like them. Everything changed after that. I set myself the goal of making the New Zealand team before I turned 18, with a vision in my young head of travelling overseas and representing my country.

NATIONAL TEAM

Then, just as I turned 13, I was selected! I wasn’t expecting it at all. What made it doubly exciting was that Jonas made the team too. I think it’s the first time a brother and sister combo have ever been selected together. Can you imagine the excitement in our house? I have been selected to represent my country each year since then, and this year I won the bronze medal in Portugal in the U16 girls’ division. It was beyond my dreams to make it to the final, surfing with the best in the world at Praia do Monte Verde, where a large swell pounded the beach break. Even though the conditions improved throughout the competition, the waves were pretty unruly and hard to read, so I was seriously stoked to get a medal.

FAMILY

I’m so lucky to have four supportive parents. My mum, Anna, and her partner, Paul, are yoga instructors, so have always practised lots of yoga with us. It’s great for keeping your body strong, open and flexible. All those extra things really give you an edge when competing at a high level. And Mum and Paul are always ready with a good massage after we’ve been training hard. So we can dissect our technique, Jo spends hours filming us, and offers fantastic analytical advice. She’s incredibly supportive of women surfers, having been with Surfing New Zealand for so many years.

My dad has always coached our sports teams, like many other supportive parents, and he and Jo drive us for miles looking for swell. He and Jo have given up so much of themselves to help us succeed. My dad’s always out in the surf. In fact, he’s the biggest grom I know. He’ll be out there when it’s absolute crap, just loving it, for hours on end. I’d surf every day of my life if I could. It’s an addiction, a habit your body and mind craves. I love the exhilaration that comes from the challenge of riding waves and speeding along the face. I’d like to have a go at the professional junior circuit in Australia. Finding funding for that is the biggest challenge. And I also have next year’s World Champs on my mind. I want to win it.”

ELIN’S ACHIEVEMENTS

2011 U12 Women’s Champion, Taranaki. 2013 Ranked 3rd nationally (U17 girls).

2013 New Zealand Primary Schools U13 Girl’s Champion.

2014 U16 Women’s Champion, Gisborne. 2014 Vissla ISA World Junior Surfing Championship, Ecuador (U16 girls), 13th place.

2015 Ranked 2nd nationally (U17 girls).

2015 Vissla ISA World Junior Surfing Championship, California (U16 girls), 16th place. Best result for New Zealand team that year.

2015 Ranked 7th nationally (open women’s).

2016 Ranked 2nd nationally (U17 girls).

2016 U16 and U18 Women’s Champion, and placed 3rd in Open Women’s, Dunedin.

2016 Vissla ISA World Junior Surfing Championship, Azores, Portugal (U16 girls, 3rd place. First Kiwi in 9 years to reach podium, best result in New Zealand team that year, helping New Zealand team to finish 10th overall.

2016 New Zealand Secondary Schools U18 Champion, Raglan Academy Competition.

2016 Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Secondary School Sportswoman of the Year for Bay of Plenty.

JONAS

“Surfing is my passion, and I’m completely committed to it. Elin and I are at Mount College during the week, but all weekend we are on the road or at home, surfing. We have done this for as far back as I can remember.

THE HOME FRONT